|

(1700 words; 8 minute read.) It’s September 21, 2020. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg has just died. Republicans are moving to fill her seat; Democrats are crying foul. Fox News publishes an op-ed by Ted Cruz arguing that the Senate has a duty to fill her seat before the election. The New York Times publishes an op-ed on Republicans’ hypocrisy and Democrats’ options. Becca and I each read both. I—along with my liberal friends—conclude that Republicans are hypocritically and dangerous violating precedent. Becca—along with her conservative friends—concludes that Republicans are doing what needs to be done, and that Democrats are threatening to violate democratic norms (“court packing??”) in response. In short: we both see the same evidence, but we react in opposite ways—ways that lead each of us to be confident in our opposing beliefs. In doing so, we exhibit a well-known form of confirmation bias. And we are rational to do so: we both are doing what we should expect will make our beliefs most accurate. Here’s why.

8 Comments

(2000 words; 9 minute read.) So far, I’ve laid the foundations for a story of rational polarization. I’ve argued that we have reason to explain polarization through rational mechanisms; showed that ambiguous evidence is necessary to do so; and described an experiment illustrating this possibility.

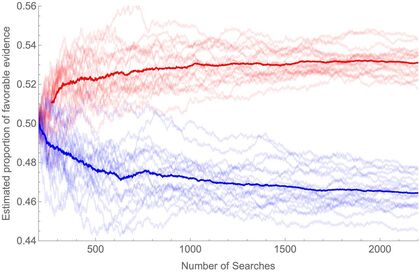

Today, I’ll conclude the core theoretical argument. I'll give an ambiguous-evidence model of our experiment that both (1) explains the predictable polarization it induces, and (2) shows that such polarization can in principle be profound (both sides end up disagreeing massively) and persistent (neither side is changes their opinion when they discover that they disagree). With this final piece of the theory in place, we’ll be able to apply it to the empirical mechanisms that drive polarization, and see how the polarizing effects of persuasion, confirmation bias, motivated reasoning, and so on, can all be rationalized by ambiguous evidence. Recall our polarization experiment. (2300 words, 12 minute read.)

So far, I've (1) argued that we need a rational explanation of polarization, (2) described an experiment showing how in principle we could give one, and (3) suggested that this explanation can be applied to the psychological mechanisms that drive polarization. Over the next two weeks, I'll put these normative claims on a firm theoretical foundation. Today I'll explain why ambiguous evidence is both necessary and sufficient for predictable polarization to be rational. Next week I'll use this theory to explain our experimental results and show how predictable, profound, persistent polarization can emerge from rational processes. With those theoretical tools in place, we'll be in a position to use them to explain the psychological mechanisms that in fact drive polarization. So: what do I mean by "rational" polarization; and why is "ambiguous" evidence the key? It’s standard to distinguish practical from epistemic rationality. Practical rationality is doing the best that you can to fulfill your goals, given the options available to you. Epistemic rationality is doing the best that you can to believe the truth, given the evidence available to you. It’s practically rational to believe that climate change is a hoax if you know that doing otherwise will lead you to be ostracized by your friends and family. It’s not epistemically rational to do so unless your evidence—including the opinions of those you trust—makes it likely that climate change is a hoax. My claim is about epistemic rationality, not practical rationality. Given how important our political beliefs are to our social identities, it’s not surprising that it’s in our interest to have liberal beliefs if our friends are liberal, and to have conservative beliefs if our friends are conservative. Thus is should be uncontroversial that the mechanisms that drive polarization can be practically rational—as people like Ezra Klein and Dan Kahan claim. The more surprising claim I want to defend is that ambiguities in political evidence make it so that liberals and conservatives who are doing the best they can to believe the truth will tend to become more confident in their opposing beliefs. To defend this claim, we need concrete theory of epistemic rationality. (2200 words; 10 min read)

When Becca and I left our home town in central Missouri 10 years ago, I made my way to a liberal university in the city, while she made her way to a conservative college in the country. As I’ve said before, part of what’s fascinating about stories like ours is that we could predict that we’d become polarized as a result: that I’d become more liberal; she, more conservative. But what, exactly, does that mean? In what sense have Americans polarized—and in what sense is the predictability of this polarization new? That’s a huge question. Here’s the short of it. (1700 words; 8 minute read)

The core claim of this series is that political polarization is caused by individuals responding rationally to ambiguous evidence. To begin, we need a possibility proof: a demonstration of how ambiguous evidence can drive apart those who are trying to get to the truth. That’s what I’m going to do today. I’m going to polarize you, my rational readers. (1700 words; 8 minute read.) [9/4/21 update: if you'd like to see the rigorous version of this whole blog series, check out the paper on "Rational Polarization" I just posted.] A Standard Story

I haven’t seen Becca in a decade. I don’t know what she thinks about Trump, or Medicare for All, or defunding the police. But I can guess. Becca and I grew up in a small Midwestern town. Cows, cornfields, and college football. Both of us were moderate in our politics; she a touch more conservative than I—but it hardly mattered, and we hardly noticed. After graduation, we went our separate ways. I, to a liberal university in a Midwestern city, and then to graduate school on the East Coast. She, to a conservative community college, and then to settle down in rural Missouri. I––of course––became increasingly liberal. I came to believe that gender roles are oppressive, that racism is systemic, and that our national myths let the powerful paper over the past. And Becca? (2500 words; 11 minute read.)

Last week I had back-to-back phone calls with two friends in the US. The first told me he wasn’t too worried about Covid-19 because the flu already is a pandemic, and although this is worse, it’s not that much worse. The second was—as he put it—at “DEFCON 1”: preparing for the possibility of a societal breakdown, and wondering whether he should buy a gun. I bet this sort of thing sounds familiar. People have had very different reactions to the pandemic. Why? And equally importantly: what are we to make of such differences? The question is political. Though things are changing fast, there remains a substantial partisan divide in people’s reactions: for example, one poll from early this week found that 76% of Democrats saw Covid as a “real threat”, compared to only 40% of Republicans (continuing the previous week’s trend). What are we to make of this “pandemic polarization”? Must Democrats attribute partisan-motivated complacency to Republicans, or Republicans attribute partisan-motivated panic to Democrats? I’m going to make the case that the answer is no: there is a simple, rational process that can drive these effects. Therefore we needn’t—I’d say shouldn’t—take the differing reaction of the “other side” as yet another reason to demonize them. 2400 words; 10 minute read.

The Problem We all know that people now disagree over political issues more strongly and more extensively than any time in recent memory. And—we are told—that is why politics is broken: polarization is the political problem of our age. Is it? |

Kevin DorstPhilosopher at MIT, trying to convince people that their opponents are more reasonable than they think Quick links:

- What this blog is about - Reasonably Polarized series - RP Technical Appendix Follow me on Twitter or join the newsletter for updates. Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed