|

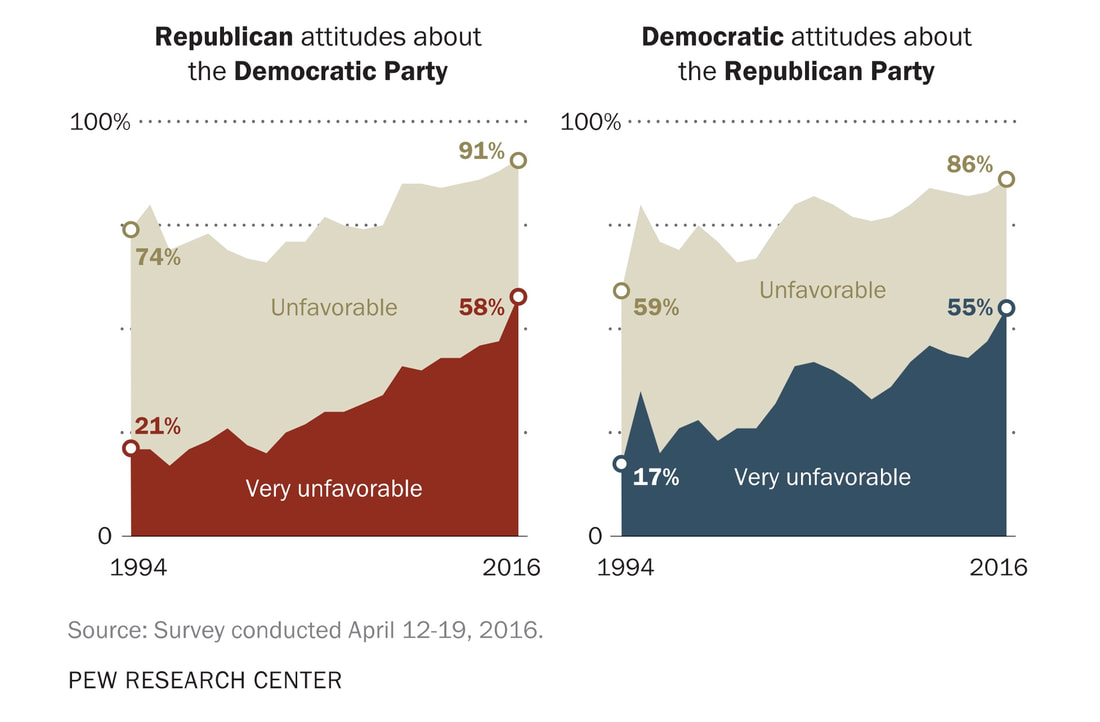

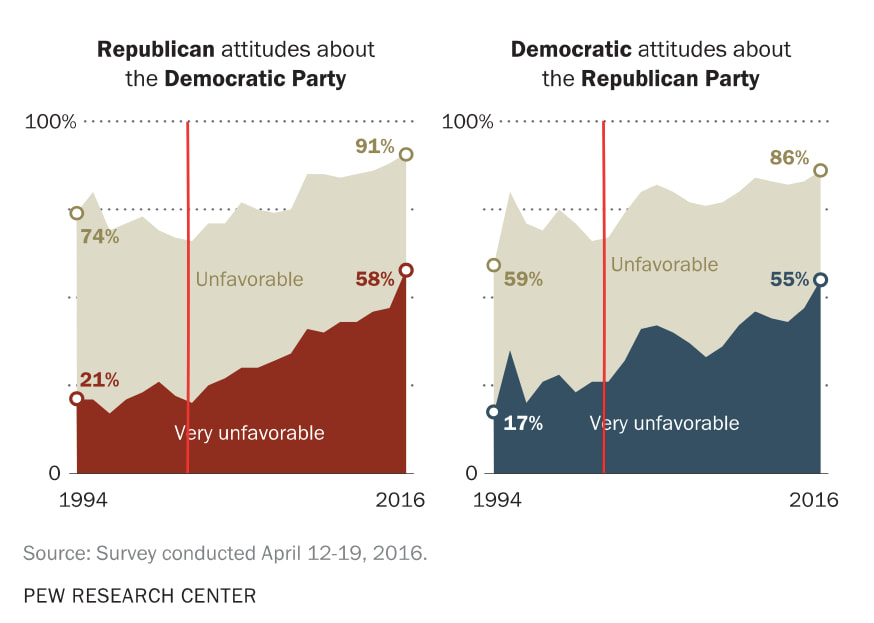

2400 words; 10 minute read. The Problem We all know that people now disagree over political issues more strongly and more extensively than any time in recent memory. And—we are told—that is why politics is broken: polarization is the political problem of our age. Is it? Polarization standardly refers to some measure of how much people disagree about a given topic—say, whether Trump is a good president. Current polling suggests that around 90% of Republicans approve of Trump, while only around 10% of Democrats do. We are massively polarized—and that is the problem. Right? Not obviously. Consider religion. On any metric of polarization, Americans have long been massively polarized on religious questions—even those that crisscross political battle lines. For example, 84% of Christians believe that the Bible is divinely inspired, compared to only 32% of the religiously unaffiliated (who now make up over a quarter of the population). Yet few in the United States think that religious polarization is the political problem of our age. Why? Because most Americans who disagree about (say) the origin of the bible have learned to get along: large majorities maintain friendships across the religious/non-religious divide, trust members of each group equally, and are happy to agree to disagree. In short: although Americans are polarized on religious questions, they do not generally demonize each other as a result. Contrast politics. Whatever your opinion about whether Trump is a good president, consider your attitude toward the large plurality who disagree with you—the “other side.” Obviously you think they are wrong—but I’m guessing you’re inclined to say more than that. I’m guessing you’re inclined to say that they are irrational. Or biased. Or (let’s be frank) dumb. You are not alone. A 2016 PEW report found that majorities of both Democrats and Republicans think that people from the opposite party are more “close-minded” than other Americans, and large pluralities think they are more “dishonest”, “immoral”, and “unintelligent.” This is new. Between 1994 and 2016 the percentage of Republicans who had a “very unfavorable” attitude toward Democrats rose from 21% to 58%, and the parallel rise for Democrats’ attitudes’ toward Republicans was from 17% to 55%: So we do have a problem, and polarization is certainly part of it. But there is a case to be made that the crux of the problem is less that we disagree with each other, and more that we despise each other as a result. In a slogan: The problem isn’t mere polarization—it’s demonization. If this is right, it’s important. If mere polarization were the problem, then to address it the opposing sides would have to come to agree—and the prospects for that look dim. But if demonization is a large part of the problem, then to address it we don’t need to agree. Rather, what we need is to recover our political empathy: to be able to look at the other side and think that although they are wrong, they are not irrational. Or biased. Or dumb. The case of religion shows that it’s possible to do this while still harboring profound disagreements: polarization doesn’t imply demonization. And that raises a question: When it comes to politics, why do we suddenly feel the need to demonize those we disagree with? How have we come to be so profoundly lacking in political empathy? The Story Here, I think, is part of the story. Though “rational animal” used to be our catch-phrase, the late 20th century witnessed a major change in the cultural narrative on human nature. The potted history:

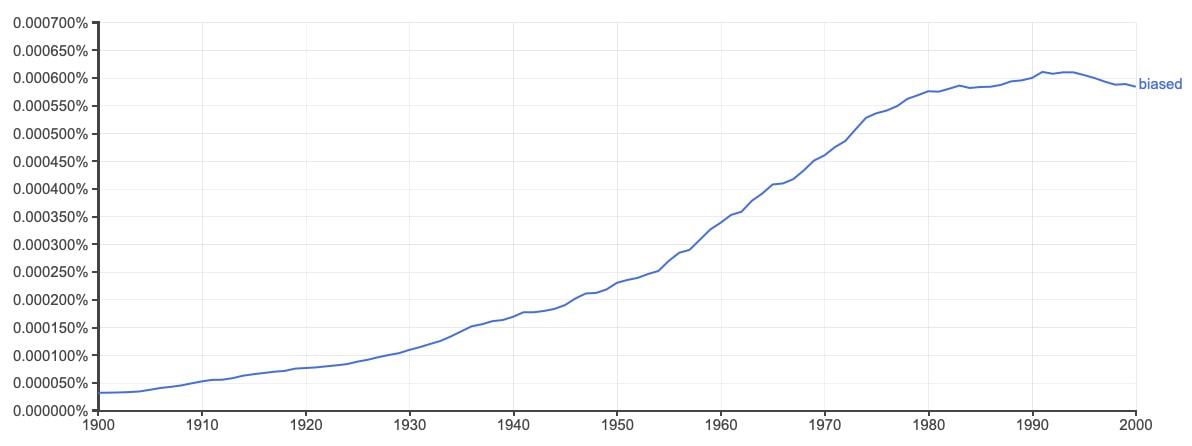

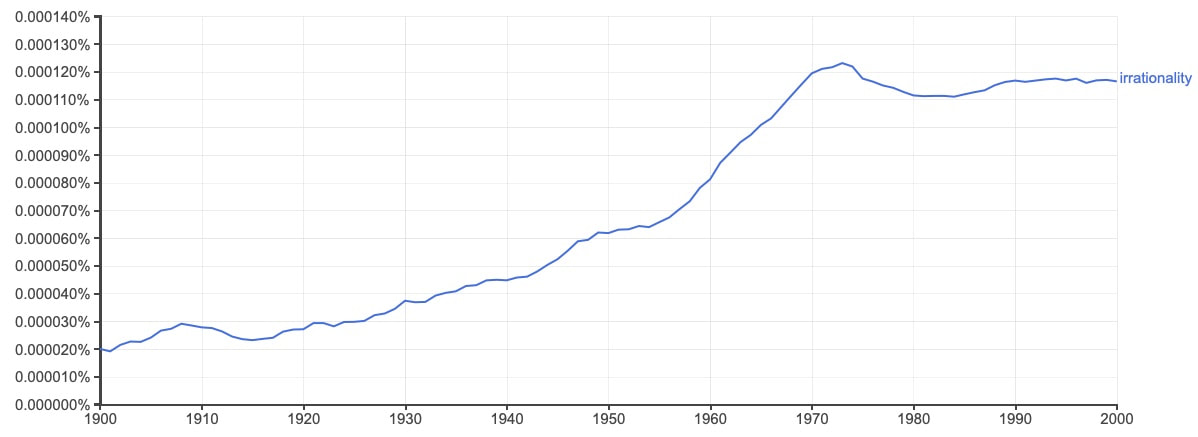

You can see the results yourself. Search “cognitive biases”, and wikipedia will offer up a list of nearly 200 of them—each one discussed by anywhere from a few dozen to over 10,000 scientific articles. You will be told that people are inept at (many of) the basic principles of reasoning under uncertainty; that they close-mindedly search for evidence that confirms their prior beliefs, and ignore or discount evidence that contravenes those beliefs; that as a result they are systematically overconfident in their opinions; and so on. This movement in psychology had a major impact both within academia and in the broader culture, fueling the appearance of (many) popular irrationalist narratives about human nature. Again, you can see the results for yourself. Using Google Ngram, graph how often terms like “biased” and “irrationality” appeared in print across the 20th century. You’ll find, for example, that “biased” was 18 times more common (percentage-wise) at the dawn of the 21st century than it was at the dawn of the 20th: Upshot: we are living in an age of rampant irrationalism. How—according to the story that I’m telling—does this rampant irrationalism feed into political demonization? Two steps. Step one is simple: we are now swimming in irrationalist explanations of political disagreement. It is not hard to see how these go. If people tend to reason their way to their preferred conclusions, to search for evidence that confirms their prior beliefs, to ignore opposing evidence, and so on, then there you have it: irrational political polarization falls out as a corollary of the informational choices granted by the modern information age. (Examples: Heuvelen 2007, Sunstein 2009, 2017; Carmichael 2018; Nguyen 2018; Lazer et al. 2018; Robson 2018; Pennycook and Rand 2019; Koerth-Baker 2019) Step two is more subtle. Suppose you read one of these articles claiming that disagreement on political issues is caused by irrational forces. Consider your opinion on some such issue—say, whether Trump is a good president. (Whatever it is, I’m guessing it’s quite strong.) Let’s imagine that you think he’s a bad president. Having come to believe that the disagreement on this question is due to irrationality, what should you now think—both about Trump, and about the rationality of various attitudes toward him? One thing you clearly should not think is: “Trump is a bad president, but I’m irrational to believe that.” (That would be what philosophers call an “akratic” belief—a paradigm instance of irrationality.) What, then, will you think? You can do one of two things:

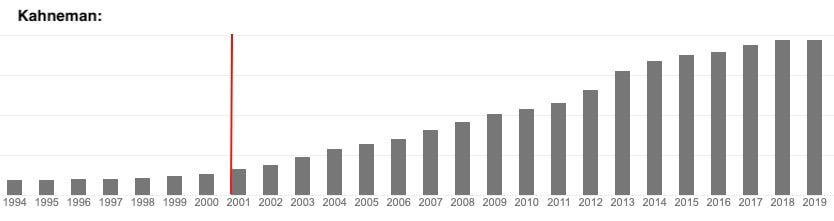

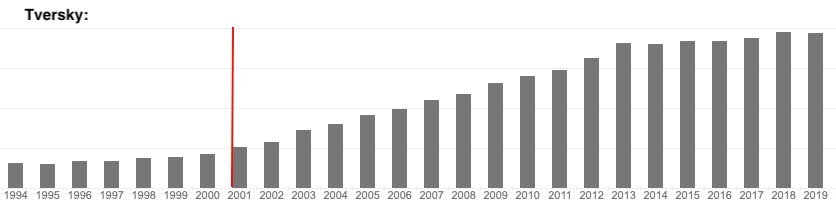

Now what will you think? You’ve just been told by an authoritative source that widespread irrationality is the cause of the massive disagreement about whether Trump is a good president. You’ve concluded that your opinion on the matter wasn’t due to massive irrationality. So whose was? Why, the other side’s, of course! You were always puzzled about how they could believe that Trump is a good president, and now you have an explanation: they were the ones who selectively ignored evidence, became overconfident, and all the rest. (Meanwhile, of course, those on the other side are going through exactly parallel reasoning to conclude that your side is the irrational one!) The result? When we come to think that irrationality caused polarization, we thereby come to think that it was the other side’s irrationality that did so. And once we view them as irrational, other terms of abuse follow. After all, irrationality breeds immorality: choices that inadvertently lead to bad outcomes are unfortunate but not immoral if they were rationally based on all the available evidence—but are blameworthy and immoral if they were irrationally based on a biased view of the evidence. So once we start thinking people are biased, we’ll also start thinking that they are “immoral”, “close-minded”, and all the rest. In a slogan: Irrationalism turns polarization into demonization. That’s the proposal, at least. Obviously it’s only part of the story in the rise of political demonization—and I don’t claim to know how big a role it’s played. (I haven’t found any literature on the connection; if you have, please share it with me!) But given how quickly discussions about political disagreements are linked to irrationalist buzz-words like “confirmation bias”, “motivated reasoning”, and the like, I would be shocked if there were no connection at all. As one small piece of evidence, consider this. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky are the founders of the modern irrationalist narrative—winning a Nobel Prize for doing so, and becoming rock-star scientists known well outside academia. Question: when did their work—which was largely conducted in the 70s and 80s—achieve this rock-star status? Again, you can see it for yourself. Use Google Scholar to graph their citations per year. Next to that, graph the trends in political demonization we’ve already seen. On each of those graphs, draw a line through 2001. Here’s what you get: Upshot: political demonization began its steady climb at the same time as the influence of the modern irrationalist narratives did. Maybe it wasn’t a coincidence.

The Project If the problem is demonization—not mere polarization—then part of the solution is to restore political empathy. And if we lack political empathy in part because of rampant irrationalist narratives, then one way to restore it is to question those narratives. That’s what I’m going to do. I’m going to write apologies—in the archaic sense of the word—for the strangers we so readily label as “biased,” “irrational,” and all the rest. How? By going back to that list of 200-or-so cognitive biases, and giving it a closer look. I’m a philosopher who studies theories and models of what thinking and acting rationally amounts to. There are (multiple) entire subfields devoted to these questions. There are no easy answers. So it’s worth taking a closer look at how we all came to take it for granted that people are irrational, biased, and (let’s be frank) dumb. I’m going to be tackling this project from different angles. This blog will be relatively exploratory; my professional work will (try to) be rigorous and well-researched; my other public writings will (try to) distill that work into an accessible form. Sometimes (as in this post) I’ll make a big-picture argument; more often, I’ll take an in-depth look at some particular empirical finding that has been taken to show irrationality. Stay tuned for topics like: overconfidence, confirmation bias, the conjunction fallacy, group polarization, the Dunning-Kruger effect, the base-rate fallacy, cognitive dissonance, and so on. As we’ll see, the bases for the claims that these phenomena demonstrate irrationality are sometimes remarkably shaky. Overgeneralizing a bit: often psychologists observe some interesting phenomenon, show how it could result from irrational processes, but move quickly over a crucial step—namely, offering a realistic model of what a rational person would think or do in the relevant situation, and an explanation of why it would be different. The reason for this is no mystery: psychologists do not spend most of their time developing realistic models of rational belief and action. Philosophers do. That’s why philosophers have things to contribute here. Because—as we’ll see—when we do the work of deploying such realistic models, often the supposedly irrational phenomenon turns out to be what we should expect from perfectly rational people. The Hope In starting this project, my hope is to contribute to a different narrative about human nature—one often voiced by a different group of cognitive scientists. These are the scientists who attempt to build machines that can duplicate even the simplest actions and inferences we humans perform every day, and discover just how fantastically difficult it is to do so. It turns out that most of the problems we solve every waking minute are objectively intractable. Every time you recognize a scene, walk across a street, or reply to a question, you perform a computational and engineering feat that the most sophisticated computers cannot. I would say that the computations required for such feats make the calculations involved in the most sophisticated rational model look like child’s play—but that would be forgetting that child’s play itself involves those same computational feats. In short: rather than resulting from a grab-bag of simple heuristics, our everyday reasoning is the result of the most computationally sophisticated system in the known universe running on all cylinders. I find this narrative compelling—far more so than the irrationalist one that (I’ll argue) it’s in competition with. That is why I am starting this project. I’m doing so with a bit of trepidation, as I’m a philosopher straying outside my comfort zone into other fields. No doubt sometimes I’ll mess it up. (When I do, please tell me!) But I think it’s worth the risk. Partly because I have things to say. But mostly because I hope to convince more people that there are still things here worth saying. How irrational are we, really? I think the question is far from settled. And part of what I’m going to be arguing is that it is a question that is sufficiently subtle to appear on the pages of the The Philosophical Review, and at the same time sufficiently consequential to appear on the pages of The New York Times. I hope you’ll come to agree. What next? If you’re an interested philosopher, reach out to me. There are a variety of people working on these topics, and I’m hoping to help build and grow that network. If you’re an interested social scientist, reach out to me. Whether it’s to inform me of literature I don’t know (good!), to correct my mistakes about it (great!), or to propose something about it we might explore together (wonderful!), I would love to hear from you. If you’re just interested, sign up for the newsletter or follow me on Twitter for updates; check out this detailed piece scrutinizing the putative evidence for overconfidence, or this bigger-picture piece on the possibility of rational polarization; and stay tuned for new posts in the coming weeks and months. PS. Thanks to Cosmo Grant, Rachel Fraser, Kieran Setiya, and especially Liam Kofi Bright for much guidance with writing this post and starting this project. It should go without saying that any mistakes (here, or to come) are my own.

26 Comments

APC

2/18/2020 09:42:10 am

Nice post. Quick question: how is the explanation of why political disagreements involve despising “the other” compatible with the putative contrast between political and religious disagreements?

Reply

KMD

2/19/2020 01:43:37 am

Good question! One clarification, and some thoughts.

Reply

RJB

2/18/2020 06:49:34 pm

This promises to be interesting. I would encourage you to consider two perspectives, which I can't quite tell if you plan to adopt.

Reply

KMD

2/19/2020 01:50:37 am

Thanks for your comment. Totally agreed, on both fronts!

Reply

2/18/2020 06:59:20 pm

Hi Kevin, I'm the guy whose book someone on Twitter recommended. I've been making both of these arguments for A LONG TIME BUT NEVER CONNECTED THEM in the way you have here.

Reply

KMD

2/19/2020 01:53:28 am

Awesome, thanks Lee! Will definitely check our your blog. (A friend also recommended a book of yours, which I will read with interest!)

Reply

Derek Baker

2/18/2020 07:38:23 pm

This is interesting, but it at least seems like the opposite of what I've seen personally. Generally it seems like people want to assume that Trump supporters, say, are ignorant or irrational, because the alternative is that they roughly know what Trump is doing, and they like it. Stupid and irrational is the charitable interpretation.

Reply

KMD

2/19/2020 02:13:34 am

Good (difficult!) question. This is something I've debated a lot, and I'm not completely sure what to think; but two main thoughts.

Reply

Don Moorr

2/19/2020 11:18:21 am

Great post! It may be worth distinguishing irrationality from error. Someone can be making sensible but erroneous inferences from the imperfect information at their disposal. My guess is that that may relate to many of your critiques of biases.

Reply

Kevin

2/19/2020 02:59:35 pm

I completely agree. One thing that I should make sure to be very clear on in the post critiquing of the overconfidence literature, for instance, is that whether or not the miscalibration is rational, still when you learn about it that should affect your confidence. That is: even if you know you are a perfectly rational Bayesian, if you learn that your confidence in your answers exceeds the proportion that are true, you should still lower your confidence in your answers.

Reply

Sydney Penner

2/19/2020 03:08:32 pm

Fascinating post! I plan to mull over it some more.

Reply

Kevin

2/20/2020 02:39:29 pm

Thanks so much for your thoughtful reply!

Reply

Sydney Penner

2/21/2020 04:28:26 pm

I'm wondering about the claim that in the asymmetric information case it makes sense for me to attribute less irrationality to myself. Another commentator pointed out that your view appears to rely on Permissivism. As it happens, I'm sympathetic to Permissivism and so also inclined to accept some version of what you're saying here. Still, it seems to me that in many political disputes this license to attribute greater irrationality to the other side will be a very limited license.

Kevin

2/23/2020 06:18:29 am

Thanks for the follow-up! I certainly agree that to get to the bottom of the dynamics here we have to go a fair way into the underlying epistemology––and it'll get quite hairy quite quick. But I think those are great questions for epistemologists!

Matt Ferkany

2/19/2020 03:23:33 pm

Really nice post and love the project. It supplies a nice structure to some problems I've been thinking about in a less structured way. I have committed to print the view that it can be virtuous to see the opposition as rational provided they are interested in reciprocal exchange. If they aren't, I am unsure whether it is right to think of them as irrational, but do think it can be a failure of virtue to worry much about engaging with them. I'd be pleased to stay apprised of your work.

Reply

Kevin

2/20/2020 02:40:33 pm

Thanks so much Matt! Could you point me to the relevant paper? Would love to read it!

Reply

Kristinn Már

2/20/2020 07:10:07 pm

Just wanted to point to a large literature on this topic, summarized in a recent Annual Review: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

Reply

Kevin

2/23/2020 06:19:11 am

Thanks!

Reply

Murali

2/21/2020 11:05:40 am

Hi Kevin. I'm looking at this from the rational disagreement angle. In order for your project to get off the ground. Permissivism, the claim that people can rationally disagree given the same total evidence must be true. However, I think it's false. There is extensive literature on this and I can't do justice to this here. So how will you handle the permissivism issue

Reply

Kevin

2/23/2020 06:28:25 am

Thanks for your question Murali!

Reply

2/25/2020 05:28:20 pm

PT Barnum is missing here. In 1994 Rush Limbaugh started his campaign of hatred and Fox News not long after. There is a sucker born every minute and conservatives have been making money off of propaganda since 1994. There is a difference between liberal bias and right wing hate. AM Radio has for decades been a concerted effort to hate liberals. I'm rather disappointed that this factor is missing from the analysis. Every AM radio has litany of "Liberals hate us", "Liberals are un-American", "Liberals are baby killers", "Liberals are communists", and on and on. These litanies are hate speech. That's what they sell for money. Everyone in politics works backwards from a desired conclusion when interpreting world events. But conservatives have no genuine self-criticism, liberals do. Take George Bush. They are not critical of him, at all. Instead they just pretend he never existed. Conservatives just criticize liberals for money. This approach sets up a false equivalence of "both sides" being the same and this is just not true. AM Hate Radio is solely the domain of conservatives because all they do is peddle hatred of liberals. Liberals are not interested in piling on with corresponding "conservatives hate us" radio. The fellow who spawned the invention of the phrase "fake news" on Facebook said he tried to make money equally with liberal and conservative audiences but it was only mostly the conservative audience that made him money. Why is that? This analysis is missing this aspect. Until and unless the hate cash machine is factored into this analysis then I fail to see how it will have the efficacy desired.

Reply

Kevin

2/27/2020 03:48:02 am

I see your concern, and I understand your frustration. I would like to flag that the point of this space is as one where people who disagree with each other can try to find common ground. So concerns like the ones you raise are perfectly legitimate, but I would like to keep them from being framed as denunciations.

Reply

Kolja

2/27/2020 02:39:16 pm

Kevin, I think that is a great response, and I think you're exactly right. If someone exclusively listens to AM talk radio and does not interact with any "liberals" with some frequency, they would not be very irrational in thinking "the liberals" are evil and irrational.

Peter Michael Gerdes

3/16/2020 12:46:54 am

I’m a bit puzzled at the role you think the academic research is playing here.

Reply

Kevin

3/20/2020 05:11:23 am

I'm not sure I agree with you that it's a communication problem. I think the terms "irrationality" and "bias" in natural language are robustly normative terms, such that if you're thinking is irrational or biased then you're not thinking as you should. I also think that there are pretty deep conceptual links between whether you are "thinking as you should", and whether you are blameworthy for how you are thinking an acting. So I'm inclined to say, first of all, that *if* psychologists intend to be using "irrational" and "biased" in a way that is disconnected from blame, then they have chosen the wrong words---that it's at best very misleading, and certainly not outsider's faults for misinterpreting them. The problem would be not with the communication of the research but with the explanation of the research itself (since the academic work is peppered with these terms and other normative variants).

Reply

Layla

6/29/2020 04:56:57 am

Thanks for a great read! I agree strongly with what you're written and I think there's a lot more here to unpack. Another main concern for me is our current tendancy to 'preach to the choir' and only listen and talk to those who share our same opinions.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Kevin DorstPhilosopher at MIT, trying to convince people that their opponents are more reasonable than they think Quick links:

- What this blog is about - Reasonably Polarized series - RP Technical Appendix Follow me on Twitter or join the newsletter for updates. Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed