|

(1400 words; 7 minute read.) The most important factor that drove Becca and me apart, politically, is that we went our separate ways, socially. I went to a liberal university in a city; she went to a conservative college in the country. I made mostly-liberal friends and listened to mostly-liberal professors; she made mostly-conservative friends and listened to mostly-conservative ones.

As we did so, our opinions underwent a large-scale version of the group polarization effect: the tendency for group discussions amongst like-minded individuals to lead to opinions that are more homogenous and more extreme in the same direction as their initial inclination. The predominant force that drives the group polarization effect is simple: discussion amongst like-minded individuals involves sharing like-minded arguments. (For more on the effect of social influence, see this post.) Spending time with liberals, I was exposed to a predominance of liberal arguments; as a result, I become more liberal. Vice versa for Becca. Stated that way, this effect can seem commonsensical: of course it’s reasonable for people in such groups to polarize. For example: I see more arguments in favor of gun control; Becca sees more arguments against them. So there’s nothing puzzling about the fact that, years later, we have wound up with radically different opinions about gun control. Right? Not so fast.

10 Comments

(1700 words; 8 minute read.) It’s September 21, 2020. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg has just died. Republicans are moving to fill her seat; Democrats are crying foul. Fox News publishes an op-ed by Ted Cruz arguing that the Senate has a duty to fill her seat before the election. The New York Times publishes an op-ed on Republicans’ hypocrisy and Democrats’ options. Becca and I each read both. I—along with my liberal friends—conclude that Republicans are hypocritically and dangerous violating precedent. Becca—along with her conservative friends—concludes that Republicans are doing what needs to be done, and that Democrats are threatening to violate democratic norms (“court packing??”) in response. In short: we both see the same evidence, but we react in opposite ways—ways that lead each of us to be confident in our opposing beliefs. In doing so, we exhibit a well-known form of confirmation bias. And we are rational to do so: we both are doing what we should expect will make our beliefs most accurate. Here’s why. Reasonably Polarized will be back next week. In the meantime, here's a guest post on the rationality of framing effects, by Sarah Fisher (University of Reading), based on a forthcoming paper of hers that asks whether the "at least" reading of number terms can yield a rational explanation of framing effects. The paper recently won Crítica's essay competition on the theme of empirically informed philosophy—congrats Sarah! 2300 words; 10 minute read. As we learn to live in the ‘new normal’, amidst the easing and tightening of local and national lockdowns, day-to-day decision-making has become fraught with difficulty. Here are some of the questions I’ve been grappling with lately:

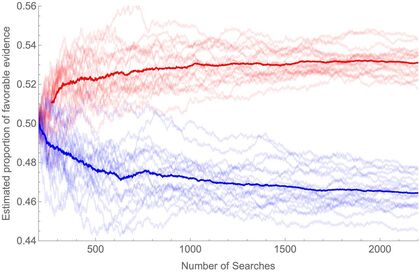

(2000 words; 9 minute read.) So far, I’ve laid the foundations for a story of rational polarization. I’ve argued that we have reason to explain polarization through rational mechanisms; showed that ambiguous evidence is necessary to do so; and described an experiment illustrating this possibility.

Today, I’ll conclude the core theoretical argument. I'll give an ambiguous-evidence model of our experiment that both (1) explains the predictable polarization it induces, and (2) shows that such polarization can in principle be profound (both sides end up disagreeing massively) and persistent (neither side is changes their opinion when they discover that they disagree). With this final piece of the theory in place, we’ll be able to apply it to the empirical mechanisms that drive polarization, and see how the polarizing effects of persuasion, confirmation bias, motivated reasoning, and so on, can all be rationalized by ambiguous evidence. Recall our polarization experiment. |

Kevin DorstPhilosopher at MIT, trying to convince people that their opponents are more reasonable than they think Quick links:

- What this blog is about - Reasonably Polarized series - RP Technical Appendix Follow me on Twitter or join the newsletter for updates. Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed