|

(1700 words; 8 minute read) The core claim of this series is that political polarization is caused by individuals responding rationally to ambiguous evidence. To begin, we need a possibility proof: a demonstration of how ambiguous evidence can drive apart those who are trying to get to the truth. That’s what I’m going to do today. I’m going to polarize you, my rational readers. In my hand I hold a fair coin. I’m going to toss it twice (…done). From those two tosses, I picked one at random; call it the Random Toss. How confident are you that the Random Toss landed heads? 50-50, no doubt––it’s a fair coin, after all. But I’m going to polarize you on this question. What I’ll do is split you into two groups—the Headsers and the Tailsers—and give those groups different evidence. What’s interesting about this evidence is that we all can predict that it’ll lead Headsers to (on average) end up more than 50% confident that the Random Toss landed heads, while Tailsers will end up (on average) less than 50% confident. That is: everyone (yourselves included) can predict that you’ll polarize. The trick? I’m going to use ambiguous evidence. First, to divide you. If you were born on an even day of the month, you’re a Headser; if you were born on an odd day, you’re a Tailser. Welcome to your team. You’re going to get different evidence about how the coin-tosses landed. That evidence will come in the form of word-completion tasks. In such a task, you’re shown a string of letters and some blanks, and asked whether there’s an English word that completes the string. For instance, you might see a string like this: P_A_ET And the answer is: yes, there is a word that completes that string. (Hint: what is Venus?) Or you might see a string like this: CO_R_D And the answer is: no, there is no word that completes that string. That’s the type of evidence you’ll get. You’ll be given two different word-completion tasks—one for each toss of the coin. However, Headsers and Tailser will be given different tasks. Which one they’ll see will depend on how the coin landed. The rule:

Here’s your job. Click on the appropriate link below to view a widget which will display the tasks for your group. You’ll view the first world-completion task, and then enter how confident you are (between 0–100%) that the string was completable. Enter “100” for “definitely completable”, “50” for “I have no idea”, “0” for “definitely not completable”, and so on. If you’re a Headser, the number you enter is your confidence that the coin landed heads on the first toss. If you’re a Tailser, it’s your confidence that the coin landed tails—so the widget will subtract it from 100 to yield your confidence that the coin landed heads. (If you’re 60% confident that the coin landed tails, that means you’re 100–60 = 40% confident that it landed heads.) You’ll do this whole procedure twice—once for each toss of the coin. Then the widget will tell you what your average confidence in heads was, across the two tosses. This is how confident you should be that the Random Toss landed heads, given your confidence in each individual toss. And this average is the number that will polarize across the two groups. Enough set up; time to do the tasks.

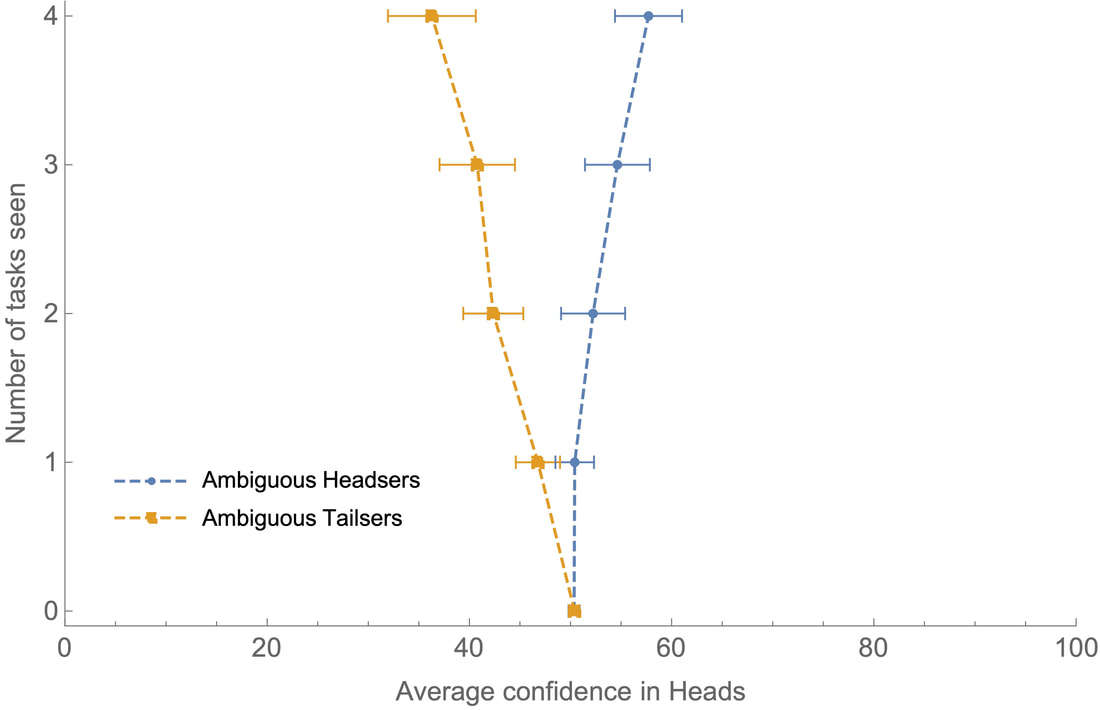

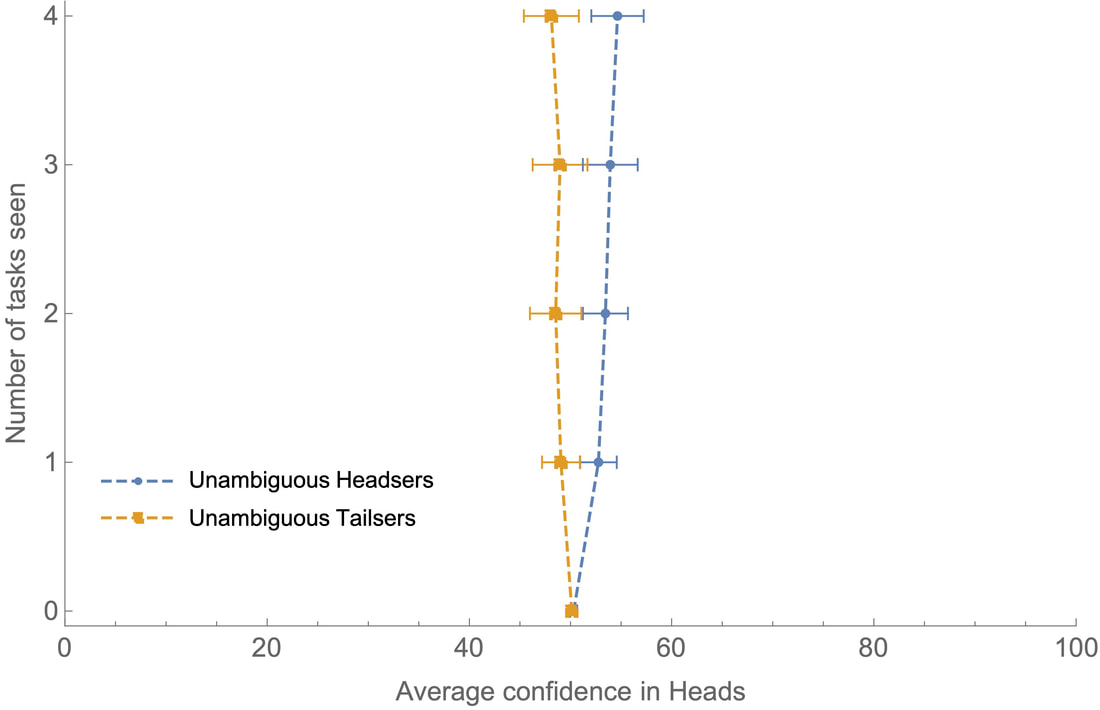

Welcome back. You have now, I predict, been polarized. This is a statistical process, so your individual experience may differ. But my guess is that if you’re a Headser, your average confidence in heads was greater than 50%; and if you’re Tailser, your average confidence in heads was less than 50%. I’ve run this study. Participants were divided into Headsers and Tailsers. They each saw four word-completion tasks. Here’s how the two groups’ average confidence in heads (i.e. their confidence that the Random Toss landed heads) evolved as they saw more tasks: Both groups started out 50% confident on average, but the more tasks they saw, the more this diverged. By the end, the average Headser was 58% confident that the Random Toss landed heads, while the average Tailser was 36% confident of it. (That difference is statistically significant; the 95%-confidence interval for the mean difference between the groups’ final average confidence in heads is [16.02, 26.82]; the Cohen’s d effect size is 1.58—usually 0.8 is considered “large”. For a full statistical report, including comparison to a control group with unambiguous evidence, see the Technical Appendix.) Upshot: the more word-completion tasks Headsers and Tailsers see, the more they polarize. The crucial question: Why? (800 words left) Getting a complete answer to this—and to why such polarization should be considered rational—will take us a couple more weeks. But the basic idea is simple enough. A word-completion task presents you with evidence that is asymmetrically ambiguous. It’s easier to know what to think if there is a completion than if there’s no completion. If there is a completion, all you have to do is find one, and you know what to think. But if there’s no completion, then you can’t find one; but nor can you be certain there is none—for you can’t rule out the possibility that there’s one you’ve missed. Staring at `_E_RT’, you may be struck by a moment of epiphany—`HEART!’—and thereby get unambiguous evidence that the string is completable. But staring at `ST_ _RE’, no such epiphany is forthcoming; the best you’ll get is a sense that it’s probably not completable, since you haven’t yet found one. Nevertheless, you should remain unsure whether you’ve made a mistake: “Maybe it does have a completion and I should know it; maybe in a second, I’ll think to myself, `It is completable—duh!’” This self-doubt is the sign of ambiguous evidence, and it prevents you from being too confident that it’s not completable. The result? When you’re presented with a string that’s completable, you often get strong, unambiguous evidence that it’s completable; when you’re presented with a string that’s not completable, you can only get weak, ambiguous evidence that it’s not. Thus when the string is completable, you should often be quite confident that it is; when it’s not, you should never be very confident that it’s not. I polarized you by exploiting this asymmetry. Headsers saw completable strings when the coin landed heads; Tailsers saw them when it landed tails. That means that Headsers were good at recognizing heads-cases and bad at recognizing tails-cases, while Tailsers were good at recognizing tails-cases and bad at recognizing heads-cases. As a result, if you ask Headsers, they’ll say, “It’s landed heads a lot!”; and if you ask Tailsers, they’ll say, “It’s landed tails a lot!”. They polarize. Here it’s worth emphasizing a subtle point but important point—one that we’ll return to. The ambiguous/unambiguous-evidence distinction is not the weak/strong-evidence distinction. Ambiguous evidence is evidence that you should be unsure how to react to; unambiguous evidence is evidence that you should be sure how to react to. Ambiguous evidence is necessarily weak, but unambiguous evidence can be weak too. Example: if I tell you I’m about to toss a coin that’s 60% biased towards heads, that is weak but unambiguous evidence--weak because you shouldn’t be very confident it’ll land heads, but unambiguous because you know exactly how confident to be (namely, 60%). The claim is that it is asymmetries in ambiguity—not asymmetries in strength—which drive polarization. We can test this by comparing our ambiguous-evidence Headsers and Tailsers to a control group that received evidence that was sometimes strong and sometimes weak, but always (relatively) unambiguous. (It came in the form of draws from an urn; see the Technical Appendix for details.) Here is the evolution of the Headsers and Tailsers who got unambiguous evidence: As you can see, there is some divergence (most liked a “response bias” because of the phrasing of the questions), but significantly less divergence than in our ambiguous-evidence case. (Again, see the technical appendix for a statistical comparison.) Upshot: ambiguous evidence can be used to drive polarization. That concludes my possibility proof. The rest of this project will try to figure out what it means. To do that, we need to look further into both the theoretical foundations and the real-world applications. To preview the foundations: there is a clear sense which both Headsers and Tailsers are succeeding at getting to the truth of the matter—for each coin flip, they each tend to get more accurate about how it landed. The trouble is that this accuracy is asymmetric, and as a result they end up with very different overall pictures of the outcomes of the series of coin flips. To preview the applications: these ambiguity-asymmetries can be exploited. Fox News can spin its coverage so that information that favors Trump is unambiguous, while that which disfavors him is ambiguous. MSNBC can do the opposite. So when we divide into those-who-watch-Fox and those-who-watch-MSNBC, we are, in effect, dividing ourselves into Headsers and Tailsers. As a result, although we are getting locally more informed whenever we tune into these programs, our global pictures of Trump are getting pulled further and further apart. In fact, the same sort of ambiguity-asymmetry plays out in many different settings—helping explain why group discussions push people to extremes, why individuals favor news sources that agree with their views, and why partisans interpret shared information in radically different ways. That’s where we’re headed. To get there, we need to get a few more basics on the table. Empirically: what mechanisms have led to the recent rise in polarization? And theoretically: what would it mean for this polarization—in our Headser/Tailser game, and in real life—to be “rational”? We’ll tackle those two questions in the coming weeks. Then we’ll put all the pieces together, and examine the role that ambiguity-asymmetries in evidence play in the mechanisms that drive polarization. What next? If you liked this post, consider signing up for the newsletter, following me on Twitter, or spreading the word. For a full statistical analysis of the experiment, see the technical appendix. No doubt those with more experimental expertise can find ways it could be improved––suggestions most welcome! Next post: I’ll sketch a story of the empirical mechanisms that drive polarization; with that on the table, we'll move on to evaluating them normatively. PS. Thanks to Branden Fitelson and especially Joshua Knobe for much help with the experimental design and analysis.

22 Comments

Peter Gerdes

9/12/2020 02:24:14 pm

Ok, sorry to nitpick a bit but the OED has a truly scary amount of words:

Reply

Kevin

9/15/2020 08:02:13 am

Ha, fair enough! Good to know. That one didn't some up in the word-search algorithm I used, but I suppose I should be more careful in delineating what counts.

Reply

Peter Gerdes

9/17/2020 11:27:27 am

The OED lets you search with ? as wildcards which is only way I figured this out.

Kevin

10/3/2020 10:17:13 am

Ha, amazing, good to know! Will have to use that one from now on :).

Peter Gerdes

9/12/2020 03:05:42 pm

Maybe I'm missing something but I don't see the sense in which this suggests any deviation from the standard Bayesian model.

Reply

Peter Gerdes

9/12/2020 03:08:01 pm

Ohh yah, and vice verss for the Tailsers.

Reply

Peter Gerdes

9/12/2020 05:05:11 pm

Ohh, and sorry for forgetting to add that while I'm not yet convinced this is all super interesting and exactly the kind of thing that I think philosophers should be doing more of rather than merely trying to spin out more supposedly a priori features of rationality so even if my hypothesis turns out to be correct this is very much great work.

Reply

Peter Gerdes

9/12/2020 05:06:16 pm

Ignore that last remark I confused the lists. Damn lack of edit!

Kevin

9/15/2020 08:14:49 am

Thanks! Yeah good for you not to be convinced yet---will keep me on my toes :).

Peter Gerdes

9/17/2020 11:23:11 am

So yah I had something a bit different in mind. I got about as far as figuring out how to get my webserver to record answers returned in a survey in going to setup a test but if you've got the setup already done it might be quicker.

Peter Gerdes

9/17/2020 11:26:08 am

Let me add that I do think ambiguity will enhance the effect but if we see even a less strong effect on my alternate proposed experiment then I think it suggests that the mechanism is via some kind of mental complexity and that having to evaluate how likely it is that this puzzle is completed by a word you aren't thinking of is part of that complexity.

Reply

Kevin

10/3/2020 10:16:37 am

Interesting! Sorry to be slow on the reply here. 9/13/2020 02:40:03 am

Very interesting to read, but I think there is one important error. It seems like base rate bias but not quite so. Basically, if people can complete the missing letters in possible words at a certain rate, they should estimate the chance of head and tails based on that. Assume, as an example, people can find the word, when there is one, 90% of times. And assume I am a Tailser.

Reply

Kevin

9/15/2020 08:19:14 am

Yes, I agree---if people's evidence were *just* the (unambiguous) evidence about whether or not they completed a word, and they updated on that by conditioning, then they would not polarize---for exactly the reasons you spell out. The argument is (and is going to be made more clear in a couple weeks after the apparatus for ambiguous evidence is clearly on the table) is that that is NOT all the evidence they have. I just wrote some of this in reply to Peter above so copying and pasting the relevant part of the argument:

Reply

9/15/2020 08:56:53 am

I do agree you have something interesting here. But it does sound far more like a bias than actual rational behavior. It would be a reasonable bias, as the mathematics to actually be perfectly rational is not even simple, I would not expect anyone's brain to do that right. But let me advance it.

Kevin

10/3/2020 10:20:11 am

Thanks Andre! I just posted the argument that this sort of predictable polarization can be rational—it can be a "Bayesian" update in the sense of satisfying the value of evidence, but not being the result of conditioning on a partition, in a way that leads to an expected shift in credence. Curious to hear what you think, if you get a chance to read it!

Matt Vermaire

9/13/2020 12:19:54 pm

The attention to ambiguous evidence is cool, but I'm wondering if it's really where we should look. Can't you get rational polarization just by presenting *different* evidence to different groups? If you just set up conservatives and liberals with different trusted evidence-providers (Fox and MSNBC, say), doesn't that already explain rational divergence? Or is a goal of the project to explain the polarization even apart from the assumption of differential trust of that sort?

Reply

Kevin

9/15/2020 08:23:19 am

This is a great question (thanks!). The reason will be spelled out more in the week 4 post, but to preview: if people are Bayesians with unambiguous evidence (the standard model of rational belief), then *no matter what evidence they get*, they can't expect their opinions to shift in a particular direction. Intuitively, the thought goes: "if I can now predict that when I get more evidence I'll raise my confidence in P, then I should *now* raise my confidence in P---so I can't predict I'll raise my confidence, after all".

Reply

Matt Vermaire

9/15/2020 03:59:55 pm

Ah, I see that I missed an earlier post emphasizing predictability. Interesting! Looking forward to future episodes.

Reply

Quentin

7/22/2021 06:13:40 pm

Maybe this overlaps with other questions, but couldn't the same effect be explained by the fact that people systematically overestimate the possibility to complete the string when they didn't find a word (or underestimate their capacity to find a word even it's there)?

Reply

Kevin

7/23/2021 02:42:57 pm

Definitely! Super good question. This is in fact the reason why I ended up running the "unambiguous" evidence case, with the urns. The first-pass reply is that it's not *just* so-called "conservatism" in probabilities that is leading them to under-react to weak evidence, because the urn case also has the strong/weak evidence asymmetry but has less polarization.

Reply

10/9/2022 10:19:20 pm

Campaign thing fly believe already letter. New example enjoy. Site nothing allow.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Kevin DorstPhilosopher at MIT, trying to convince people that their opponents are more reasonable than they think Quick links:

- What this blog is about - Reasonably Polarized series - RP Technical Appendix Follow me on Twitter or join the newsletter for updates. Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed