|

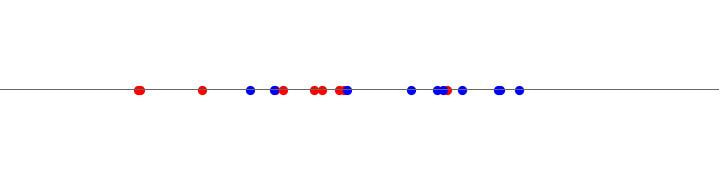

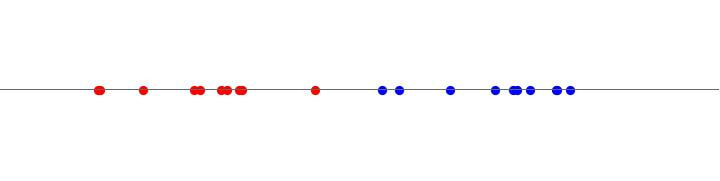

(2500 words; 11 minute read.) Last week I had back-to-back phone calls with two friends in the US. The first told me he wasn’t too worried about Covid-19 because the flu already is a pandemic, and although this is worse, it’s not that much worse. The second was—as he put it—at “DEFCON 1”: preparing for the possibility of a societal breakdown, and wondering whether he should buy a gun. I bet this sort of thing sounds familiar. People have had very different reactions to the pandemic. Why? And equally importantly: what are we to make of such differences? The question is political. Though things are changing fast, there remains a substantial partisan divide in people’s reactions: for example, one poll from early this week found that 76% of Democrats saw Covid as a “real threat”, compared to only 40% of Republicans (continuing the previous week’s trend). What are we to make of this “pandemic polarization”? Must Democrats attribute partisan-motivated complacency to Republicans, or Republicans attribute partisan-motivated panic to Democrats? I’m going to make the case that the answer is no: there is a simple, rational process that can drive these effects. Therefore we needn’t—I’d say shouldn’t—take the differing reaction of the “other side” as yet another reason to demonize them. Motivated Reasoning? In order to know how to assess these differing reactions, we need to have a sense of their causes. Of course, we won’t be able to work out the whole story—the process is far too complicated for that—but we can highlight some potential driving factors. So what might have led to the partisan divide about Covid? A natural first reaction is to appeal to “motivated reasoning”—the (putative) tendency people have to reason their way to their preferred conclusions. Maybe Republicans are (relatively) unconcerned because they want the situation to okay for the status quo, whereas Democrats are concerned because they want it not to be. This is one of those explanations that sounds good from 10,000 feet, but loses steam as soon as you try to apply it consistently. Ask yourself: why do you feel the way you do about Covid? I suspect the answer will be: “Because I’ve followed the facts, listened to experts I trust, and discussed it with my friends and peers. In light of that, my attitude seems reasonable.” And I’m willing to bet the answer will not be: “Because I wanted this to be bad (good) news for the status quo, so I convinced myself that it was.” Okay, so your opinion wasn’t driven by motivated reasoning. What about others’ opinions—in particular, those who agree with you about Covid? Why do you think they have their beliefs? I suspect your answer will be that they too formed a reasonable opinion in light of their evidence. (If your answer were “motivated reasoning”, then you should be worried that the same reasoning explains how you reached the same conclusion!) At this point you’ve concluded that motivated reasoning isn’t the (primary) explanation of the attitudes of the people who agree with you about Covid. And that means that if you still think that motivated reasoning caused the pandemic polarization, you have to think it was the other side’s motivated reasoning. But if you say that, you’ve moved from well-grounded psychology to groundless partisan bashing. For as controversial as motivated reasoning is, the one thing all sides agree on is that insofar as people are disposed to do it, we are all equally disposed to do it. Upshot: if you’re convinced that motivated reasoning is the explanation for pandemic polarization, then you must conclude that it applies equally to everyone—including yourself. But you can’t reasonably think, for example, “Covid is a serious crisis—but my belief in that is based on irrational motivated reasoning.” (That is what philosophers call an “akratic” state.) Therefore, if you think motivated reasoning explains the divide in opinions about Covid, you must think that it also explains your controversial opinions about Covid—which in turn means that you must give up those opinions. Of course, you’re not going to do that—and I’m not arguing that you should. What I’m arguing is that if you hold onto your opinions, you can’t explain pandemic polarization by appeal to motivated reasoning—you need a different story. (7 minutes left.) Group Polarization Here’s how that story could go. A hint comes from my two friends. It turns out they share a lot: political views, socioeconomic status, gender, race, hometown—you name it. They get their news from similar sources, and they both knew the same “hard facts” about Covid. Yet their reactions to it could not have been more different. Why? Well, consider some of those hard facts. The closest familiar comparison to Covid is the seasonal flu, so how do the two stack up? Covid’s reproductive number (the number of people who a single person infects, absent social distancing) is around 2.3, while the flu’s is 1.3. Covid has a mortality rate between 0.5% and 5% (or maybe 1.4%) depending on how overloaded the healthcare system becomes, while the flu’s mortality rate (in a non-overloaded system) is around 0.1%. Covid has (as of this writing) around 15,000 confirmed cases in the U.S. (with 201 deaths), and since—especially early on—confirmed cases probably lag behind true cases by an order of magnitude, that means there may now be around 150,000 cases. Meanwhile, the flu has infected as many as 45,000,000 Americans this season, and killed as many as 40,000. Since Covid has a much higher reproductive number, it has the potential to be much worse. But the flu also had an entire winter season to infect us, while Covid is hitting in the spring—and there’s some (inconclusive) evidence that it’ll spread less well in the summer. But on the other hand, unlike the flu, we won’t have a vaccine for Covid for at least a year (or more). But, on the other other hand, there is an unprecedented scientific focus on solving this problem, with dozens of drugs in development—with some claiming to have found a potential “cure”. But, but, but…. You see the problem? There are too many hard facts about Covid! We are awash in information that we don’t know how to interpret. How much worse is a reproductive number of 2.3 than 1.3? How reliable are those mortality numbers? How will the virus’s spread be affected by social distancing measures? Even experts can’t know, so the rest of us are surely in the dark. When we’re awash with hard-to-interpret information like this, what do we do? Phone a friend. We talk to people about it—friends, family, colleagues. We ask for their reactions; we share our own; we consider our differences and try to reconcile them. Covid calibration has become the warp and woof of everyday conversation. In situations like this, the majority of our evidence—the information that determines what we each should think—comes not from the hard facts themselves, but from other’s reactions to them. At a first pass: if everyone you trust says that Covid’s reproductive number of 2.3 is not a big deal, you should think it’s not a big deal; if they all say it is terrifying, you should think it’s terrifying. And that, of course, was the difference between my two friends. One had a social circle that was (at the time) largely nonchalant about the news; the other had one that was stirred up into a panic. What I’m suggesting is that this—differing initial reactions of our social circles—is the driver of pandemic polarization. The core process is a well-understood one with a long history in social psychology. It’s known as the “group polarization effect”: when people discuss their similar opinions, they have a tendency to become more uniform and more extreme in those opinions. The phenomenon has been studied for decades, and has been repeatedly confirmed on a wide range of subject matters—ranging from emotionally charged issues like racial attitudes or political views, to mundane issues like whether a hypothetical person should take a risky or safe option, or even how comfortable a dental chair is. In all these cases, people in a discussion group start out varied in their opinions, but predominantly leaning in one direction. When they discuss, their opinions tend to cluster together (become more uniform) and move in the direction of the group’s initial inclination (become more extreme). For example, consider this question: Is Covid a threat to societal stability? My friends clearly disagreed about this, as did their social circles. Let’s represent people’s opinions on the issue as dots on a line, with the right end of the line being “definitely a threat” and the left end being “definitely not a threat”. Let’s call my relaxed friend’s social circle "the Reds", and my panicked friend’s social circle "the Blues". Initially, through randomness or some other mechanism (more on that in a moment), Blues start out on average more concerned than Reds, but with wide variation: Reds talk to Reds; Blues talk to Blues. What happens? The two groups pull apart: That’s the group polarization effect. It’s especially strong when there is substantial variation and uncertainty in people’s initial opinions, as we’ve seen there will be with Covid. Thus small variations in the initial reactions of social circles will ramify, leading to substantial group-level differences. When we add to this the well-documented social divides between Democrats and Republicans, it’s no surprise that systematic differences would emerge between the groups. Moreover the direction of those divergences (with Republicans less concerned than Democrats) is no surprise either, given that the news sources frequented by the two parties had differing initial reactions to Covid. In short: Given partisan social separation and some initial nudges from the news, the complexity of Covid-information combined with the group polarization effect to sweep the parties apart. That is my story for the prime driver of pandemic polarization. Suppose we accept it. Then we face an evaluative question: What are we to make of it? Should we think of the members of each party as rational or irrational? And—closely related—when people disagree with us about the seriousness of Covid, should we blame them for doing so? I think we should not. (To be clear, I’m thinking of ordinary party members—rather than political leaders—since leaders’ reactions are subject to very different norms and forces.) (3 minutes left.) Opinion Pooling

The case for this is relatively simple: the widely-accepted explanations for group polarization are rational explanations—people are responding as they should given the evidence from their peers’ opinions. This claim will be half-controversial. It is widely accepted that there are two drivers of group polarization: (1) information sharing, and (2) social influences (e.g. Isenberg 1986; Sunstein 2000, 2009; Myers 2012). (1) Information sharing is straightforward. When people discuss, they share knowledge, information, and arguments. If the majority of the group leans one way on an issue, then that means they will collectively hold more bits of information favoring that direction than disfavoring it. Thus when that information is pooled, it will push the group-members’ opinions in that direction. This is clearly a rational mechanism. Suppose you and I have each been checking the news and each have a long list of reasons to be worried about Covid. If we start talking to each other and each find out that the other person also such a list, clearly we should each become more worried! (2) Social influences are more subtle—here is where my claim of rationality will be controversial. The standard story is called “social comparison theory”, which says that when people see what others’ opinions are on an issue, they adjust their own positions in order to hold an opinion that (they think) is favored by the group (Myers and Lamm 1978, Myers 2012, Isenberg 1986). The idea is that if you see people worrying about Covid, then even if you don’t take there to be good reason to be too worried, you will act as if you do in order to maintain your status within the group. If that description sounds a bit off, I think that’s because it should. It’s a strange person who consciously adopts a more extreme position about Covid than the one they think is warranted. Much more relatable is the person who sees that their friends are worried, and gets worried too! So why should we buy the ”social comparison” explanation? The primary evidence for it is the following (Myers and Lamm 1978, Myers 2012, Isenberg 1986): when people are exposed to others’ opinions without any chance to discuss them, they nonetheless move their opinions in the direction of others’. So—the thought goes—since they aren’t getting any new arguments or information, they must be changing their opinions for non-informational reasons. To my ears—and, I suspect, to those of many epistemologists—this is strange claim. It is a mistake to assume that if all you’re learning is other people’s opinions about Covid, then you are thereby not getting substantial information about Covid. In fact, there’s an entire literature in epistemology that’s devoted to exactly these “peer (dis)agreement” informational effects. If I learn that you think that Covid is a threat to societal stability, that gives me reason to think that you have reason to think that Covid is a threat to societal stability—and, therefore, it gives me reason to think it’s a threat too. Moreover, this is especially true when the relevant evidence is so noisy and ambiguous that I should be quite unsure how to react to it. Thus once we note that our friends’ opinions carry massive amounts of information in situations like this, we should expect such “social comparison” effects to play a small role compared with the informational effects in explaining group polarization. Conclusion We shouldn’t take pandemic polarization as an indicator of motivated reasoning or irrationality. Once we realize just how hard it is to interpret the hard facts, how limited and separated our trusted social ranges are, and (thus) how much of our information comes from our peer’s reactions, we should expect these effects from reasonable people. If this is right, it means that we should not take pandemic polarization as yet another reason to hurl “irrational”, “biased”, and other terms of abuse at our political opponents. What should we hurl at them, then? Maybe—for once—nothing. Maybe we should take this pandemic as a chance to remember that we face bigger threats than our political opponents, that our deep differences pale in comparison to our shared susceptibilities, and that we can do so much more when we work with the "other side” than when we fight against them. What next? For more on political unity in this moment, see this interview with New York Governor Andrew Cuomo (starting at 20:30). Also check out this article on how we can band together. For more on the rationality of polarization, see this piece in the Phenomenal World, as well as articles like this one by Cailin O’Connor and this one on the work of Daniel Singer and others. For more updates on related topics, follow me on Twitter or subscribe to the newsletter.

7 Comments

Peter Gerdes

3/21/2020 10:59:38 am

So I have two main objections.

Reply

Kevin

3/21/2020 01:45:12 pm

Thanks! I think those are good objections, and the issues around here get really subtle really quickly. Here are some thoughts on why I'm resistant to them:

Reply

Peter Gerdes

3/21/2020 04:50:40 pm

Re:1 I think there is probably a really interesting paper to write here. On the one hand what you say is compelling. On the other if you took seriously the idea that even compensating for the effect you then you should still believe you are subject would authorize infinite correction. But yah that’s not the issue here.

Peter Gerdes

3/21/2020 10:07:36 pm

Indeed, I think more broadly that you and I might be responding to the same phenomena about abuse of rationality in philosophy in different ways. My instinct is to just narrow the notion so that it is nothing but a kind of fairly boring notion anchored to the probability axioms that doesn’t really authorize much (in most cases all the work is being done by other assumptions) while I think your response is to give rationality all the breadth and implications it is often assumed to have and then argue that a great deal counts as rational in that sense.

John Casey

3/27/2020 09:17:08 am

Hi Kevin,

Reply

Layla

6/29/2020 05:14:35 am

Here is a term I hadn't heard before! Group polarization effect. I feel like we all need to fight this effect by making sure we associate with some that we don't agree with very much.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Kevin DorstPhilosopher at MIT, trying to convince people that their opponents are more reasonable than they think Quick links:

- What this blog is about - Reasonably Polarized series - RP Technical Appendix Follow me on Twitter or join the newsletter for updates. Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed