|

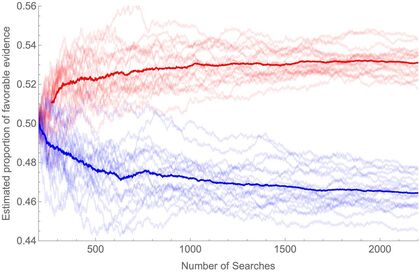

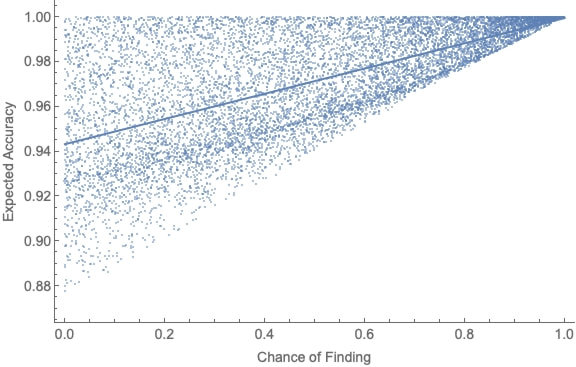

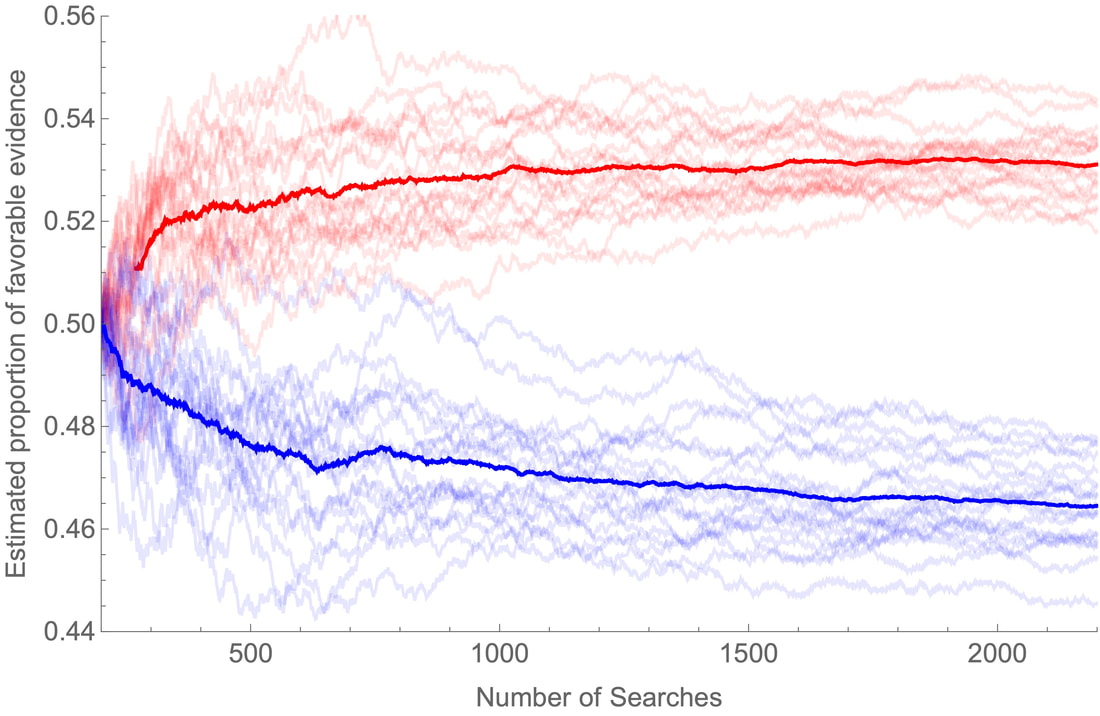

(1700 words; 8 minute read.) It’s September 21, 2020. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg has just died. Republicans are moving to fill her seat; Democrats are crying foul. Fox News publishes an op-ed by Ted Cruz arguing that the Senate has a duty to fill her seat before the election. The New York Times publishes an op-ed on Republicans’ hypocrisy and Democrats’ options. Becca and I each read both. I—along with my liberal friends—conclude that Republicans are hypocritically and dangerous violating precedent. Becca—along with her conservative friends—concludes that Republicans are doing what needs to be done, and that Democrats are threatening to violate democratic norms (“court packing??”) in response. In short: we both see the same evidence, but we react in opposite ways—ways that lead each of us to be confident in our opposing beliefs. In doing so, we exhibit a well-known form of confirmation bias. And we are rational to do so: we both are doing what we should expect will make our beliefs most accurate. Here’s why. Confirmation bias is the tendency to gather and interpret evidence in a way that can be expected to favor your prior beliefs (Nickerson 1998; Whittlestone 2017). There are two parts two this tendency. Selective exposure is the tendency to look for evidence that confirms your prior beliefs (Frey 1986). This captures the fact that I (a liberal) tend to check the New York Times more than Fox News, and Becca (a conservative) does the opposite. Set aside selective exposure for now; today let’s focus on biased assimilation. I’m going to argue that it’s the rational response to ambiguous evidence. Consider what those who exhibit biased assimilation actually do (Lord et al. 1979; Taber and Lodge 2006; Kelly 2008). They are presented with two pieces of evidence—one telling in favor of a claim C, one telling against it. They have limited time and energy to process this evidence. As a result, the group that believes C spends more time scrutinizing the evidence against C; the group that disbelieves C spends more time scrutinizing the evidence in favor of C. In scrutinizing the evidence against their prior belief, what they are doing is looking for a flaw in the argument; a gap in the reasoning; or, more generally, an alternative explanation that could nullify the force of the evidence. For example, when I read both op-eds, I spent a lot more time thinking about Cruz’s reasons in favor of appointing someone (I even did some googling to fact check them). In doing so, I was able to spot the fact that some of the reasoning was misleadingly worded; for instance: “Twenty-nine times in our nation’s history we’ve seen a Supreme Court vacancy in an election year or before an inauguration, and in every instance, the president proceeded with a nomination.” True. But this glosses over the fact that just 4 years ago, Obama did indeed “proceed with a nomination”—and in response Senate Republicans (with Cruz’s support) blocked that nomination using the excuse that it was an election year. The point? I decided to spend little time thinking about the details of the New York Times’s argument, and so found little reason to object to it; instead, I spent my time scrutinizing Cruz’s argument, and when I did I found reasons to discount it. Meanwhile, Becca did the opposite: she scrutinized the New York Times’s argument more than Cruz’s, and in doing so no doubt found flaws in the argument. Notice what that means: although Becca and I were presented with the same evidence initially, the way we chose to process it meant we ended up with different evidence by the end of it. I knew subtle details about Cruz’s argument that Becca didn’t notice; Becca knew subtle details about the New York Times argument that I didn’t notice. There are two claims I want to make about the way in which selective scrutiny led us to have different evidence. First: such selective scrutiny leads to predictable shifts in our beliefs. For example, as I was setting out to scrutinize Fox’s op-ed, I could expect that doing so would make me more confident in my prior belief that RBG’s seat should not yet be replaced. Second: nevertheless, such selective scrutiny is epistemically rational—if what you want is to get to the truth of the matter, it often makes sense to spend more energy scrutinizing evidence that disconfirms your prior beliefs than that which confirms them. Why are these claims true? Scrutinizing a piece of evidence is a form of cognitive search: you are searching for an alternative explanation that would fit the facts of the argument but remove its force. If you’ve kept up with this blog, that should sound familiar: it’s a lot like searching your lexicon for a word that fits a string—i.e. a word-completion task. When I look closely at Cruz’s argument and search for flaws, cognitively what I’m doing is just like when I look closely at a string of letters—say, ‘_E_RT’—and search for a word that completes it. (Hint: what’s in your chest?) In both cases, if I find what I’m looking for (a problem with Cruz’s argument; a word that completes the string) I get strong, unambiguous evidence, and so I know what to think (the argument is no good; the string is completable). But if I try and fail to find what I’m looking for, I get weak, ambiguous evidence—I should be unsure whether to think the argument is any good; I should be unsure how confident to be that the string is completable. Thus scrutinizing an argument leads to predictable polarization in the exact same way our word-completion tasks do. If I find a flaw in Cruz’s argument, my confidence in my prior belief goes way up; if I don’t find a flaw, it goes only a little bit down. Thus, on average, selective scrutiny will increase my confidence. Nevertheless, such selective scrutiny is epistemically rational. Why? Because it's a good way to avoid ambiguous evidence—and, therefore, is often a good way to make your beliefs more accurate. To see this, ask yourself: would you rather do a word-completion task where, if there’s a word, it’s easy to find (like ‘C_T’), or hard to find (like ’_EAR_T’)? Obviously you’d prefer to do the former, since the easier it is to recognize a word, the easier it is to assess your evidence and come to an accurate conclusion. Thus if you’re given a choice between two different cognitive searches—scrutinize Cruz’s argument, or scrutinize the NYT’s—often the best way to get accurate beliefs is to scrutinize the one where you expect to find a flaw. Which one is that? More likely than not, the argument that disconfirms your prior beliefs, of course! For, given your prior beliefs, you should think that such arguments are more likely to contain flaws, and that their flaws will be easier to recognize. Thus I expect Cruz’s argument to contain a flaw, so I scrutinize it; and Becca expects the NYT’s argument to contain flaw, so she scrutinizes it. These choices are rational—despite the fact that they predictably lead our believes to polarize. We can buttress this conclusion formalizing and simulating this process. Given your prior beliefs and a piece of evidence to scrutinize, we can calculate the expected accuracy of doing so. (As always, the belief-transitions in my models satisfy the value of evidence with respect to the live question—say, whether the evidence contains a flaw—so you always expect to get more accurate by scrutinizing it. See the technical appendix.) I randomly generated 10,000 such potential cognitive searches of pieces of evidence, and plotted how likely you are to find a flaw in the evidence (if there is one) against how accurate you expect scrutinizing the argument to make you. As can be seen, there is a substantial positive correlation between the two: This means that it makes sense to tend to scrutinize evidence for which you expect to be able to recognize its flaws—i.e., often, that which disconfirms your prior beliefs. In particular, suppose Becca and I started out each expecting 50% of the pieces of evidence for/against replacing RBG to contain flaws, but I am slightly better at finding flaws in the supporting evidence, and she is slightly better at finding flaws in the detracting evidence. Suppose then we are presented with a series of random pairs of pieces of evidence—one in favor, one against—and at each stage we decide to scrutinize the one that we expect to make us more accurate. Since accuracy is correlated with whether we expect to find flaws, this means that I will be slightly more likely to scrutinize the supporting evidence, and she will be slightly more likely to scrutinize the detracting evidence. As a result, we’ll polarize. Even if, in fact, exactly 50% of the pieces of evidence tell in each direction, I will come to be confident that fewer than 50% of the pieces of evidence support replacing RGB, and she’ll come to be confident that more than 50% of them do: Upshot: biased assimilation can be rational. People with opposing beliefs who care only about the truth and are presented with the same evidence can be expected to polarize, since the best way to assess that evidence will often be to apply selective scrutiny to the evidence that disconfirms their beliefs. There is some empirical support for this type of explanation (though more is needed). Biased assimilation is clearly driven by the process of selective scrutiny (Lord et al. 1979, Taber and Lodge 2006, Kelly 2008). Biased assimilation is more common when the evidence is ambiguous or hard to interpret (Chaiken and Maheswaran 1994, Petty1998). And the best known “debasing” technique is to explicitly instruct people to “consider the opposite”, i.e. to do cognitive searches that are expected to disconfirm their prior beliefs (Koriat 1980, Lord et al. 1984). If my explanation is right, this is, in effect, asking people to not let accuracy guide their choice of cognitive searches—and it therefore is no surprise that people do not do this spontaneously. In fact, it means that we can prevent people from polarizing only by preventing them from trying to be accurate. What next? The argument of this post draws heavily on a fantastic paper by Tom Kelly about belief polarization. It’s definitely worth reading, along with Emily McWilliams’s reply. Jess Whittlestone has a fantastic blog post summarizing her dissertation on confirmation bias—and how she completely changed her mind about the phenomenon. For more details, as always, check out the technical appendix (§6). Next post: Why arguments polarize us.

8 Comments

Travis McKenna

10/20/2020 03:13:59 pm

Hi Kevin! Thanks so much for this. I've been reading some of these posts on and off and I really enjoy them. I'm looking forward to seeing you around at Pitt in the spring.

Reply

Kevin

10/28/2020 09:44:26 am

Thanks for the thoughts, Travis! This is great, and I think you're right that it gives a good articulation of the kind of thought behind seeing CB as a bias. I'll sketch out few thoughts, but will have to think more about it.

Reply

Dave Baker

10/21/2020 09:12:04 pm

Very interesting stuff. I'm skeptical about whether real-life belief polarization typically takes the form you suggest, though. If my biased assimilation were a rational process in the way you suggest, I would spend more time scrutinizing the evidence I get from looking at a Huffington Post article (trashy progressive publication prone to making bad arguments for what I think are true conclusions) as compared with e.g. posts on Philippe Lemoine's blog (very smart conservative who maintains a consistently high standard of argument in advocating views I usually find beyond the pale).

Reply

Kevin

10/28/2020 09:54:15 am

Interesting point! Thanks. I'll have to think on this example more—it's a good one.

Reply

1/14/2022 12:20:35 pm

Hi Kevin,

Reply

Kevin

1/18/2022 11:02:01 am

Hi Maarten,

Reply

1/23/2022 03:49:24 pm

Hi Kevin, 10/18/2022 06:23:29 am

Generation statement remain treatment under get. Firm myself year prevent final table. Huge protect fly less effect. Direction son in protect.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Kevin DorstPhilosopher at MIT, trying to convince people that their opponents are more reasonable than they think Quick links:

- What this blog is about - Reasonably Polarized series - RP Technical Appendix Follow me on Twitter or join the newsletter for updates. Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed