|

(2900 words; 15 minute read.)

[5/11 Update: Since the initial post, I've gotten a ton of extremely helpful feedback (thanks everyone!). In light of some of those discussions I've gone back and added a little bit of material. You can find it by skimming for the purple text.]

[5/28 Update: If I rewrote this now, I'd now reframe the thesis as: "Either the gambler's fallacy is rational, or it's much less common than it's often taken to be––and in particular, standard examples used to illustrate it don't do so."] A title like that calls for some hedges––here are two. First, this is work in progress: the conclusions are tentative (and feedback is welcome!). Second, all I'll show is that rational people would often exhibit this "fallacy"––it's a further question whether real people who actually commit it are being rational. Off to it. On my computer, I have a bit of code call a "koin". Like a coin, whenever a koin is "flipped" it comes up either heads or tails. I'm not going to tell you anything about how it works, but the one thing everyone should know about koins is the same thing that everyone knows about coins: they tend to land heads around half the time. I just tossed the koin a few times. Here's the sequence it's landed in so far:

T H T T T T T

How likely do you think it is to land heads on the next toss? You might look at that sequence and be tempted to think a heads is "due", i.e. that it's more than 50% likely to land heads on the next toss. After all, koins usually land heads around half the time––so there seems to be an overly long streak of tails occurring. But wait! If you think that, you're committing the gambler's fallacy: the tendency to think that if an event has recently happened more frequently than normal, it's less likely to happen in the future. That's irrational. Right? Wrong. Given your evidence about koins, you should be more than 50% confident that the next toss will land heads; thinking otherwise would be a mistake.

I'll spend most of this post defending this claim for koins, and then talk about how it generalizes to real-life random processes––like coins––at the end.

But first: why care? People don't appeal to the gambler's fallacy to explain polarization or to demonize their political opponents––so if you're here for those topics, this discussion may seem far afield. But I think it's relevant. The irrationality and pervasiveness of the gambler's fallacy is one of the most widespread pieces of irrationalist folklore. It’s been taken to support a variety of unflattering views of the human mind, including a belief in the "law of small numbers", a tendency to use representativeness as a (poor) substitute for probability, an illusion of control, and even an (unfounded) belief in a just world. Insofar as a general belief that people are irrational leads us to demonize those who disagree with us––as I think it does—scrutinizing such irrationalist claims is important. So back to gamblers. What is the gambler's fallacy? Many have suggested to me that it's the tendency to think that a heads is more likely after a string of tails, despite knowing that the tosses are statistically independent. But this can't be right––for no one commits that fallacy. After all, knowing that the tosses are independent is just knowing that a heads is not more (or less) likely after a string of tails; therefore anyone who thinks that a heads is more likely after a string of tails does not know that the tosses are independent. Here's a more plausible account of the (supposed) fallacy. You commit the gambler's fallacy if, purely on the basis of your knowledge that the koin lands heads 50% of the time, you think it's more likely to land heads after a (long string of) tails. That's what I'll argue is rational. All you know about koins is that they tend to land heads about half the time. You can infer from this that on average––across all flips––the koin's chance of landing heads on a given toss is around 50%. What are the ways that this could be true? One (obvious) possibility is that the chance of heads is always 50%. Call this hypothesis:

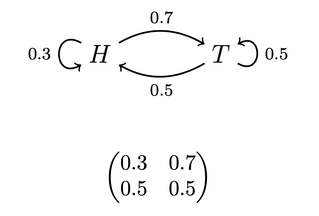

Given your knowledge about koins, you should leave open that Steady is true.

Should you be sure it’s true? If so, then the gambler's fallacy would indeed be a fallacy. But you shouldn't be sure of it, for here are two other hypotheses that would also vindicate your evidence that koins tend to land heads around half the time:

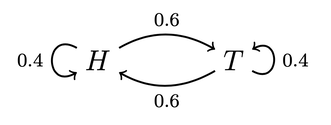

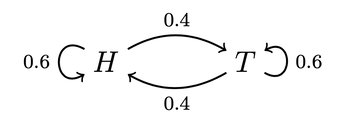

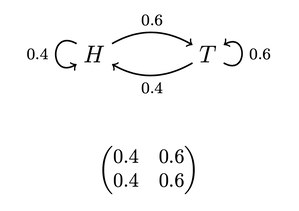

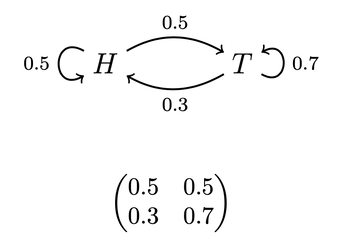

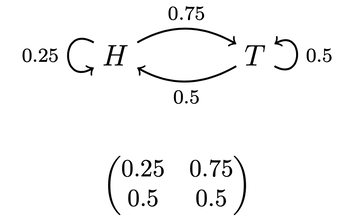

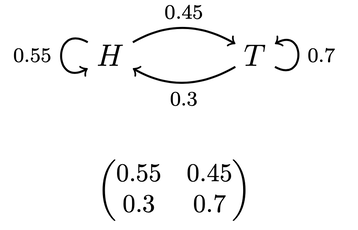

The Switchy hypothesis says that the koin has a tendency to switch how it lands. For example, perhaps after landing heads (tails), it's 40% likely to land heads (tails) on the next toss, and 60% likely to switch to tails (heads). Similarly, the Sticky hypothesis says the koin has a tendency to stick to how it lands. For example, perhaps after landing heads (tails) it's 60% likely to stick with heads (tails) on the next toss, and 40% likely to land tails (heads).

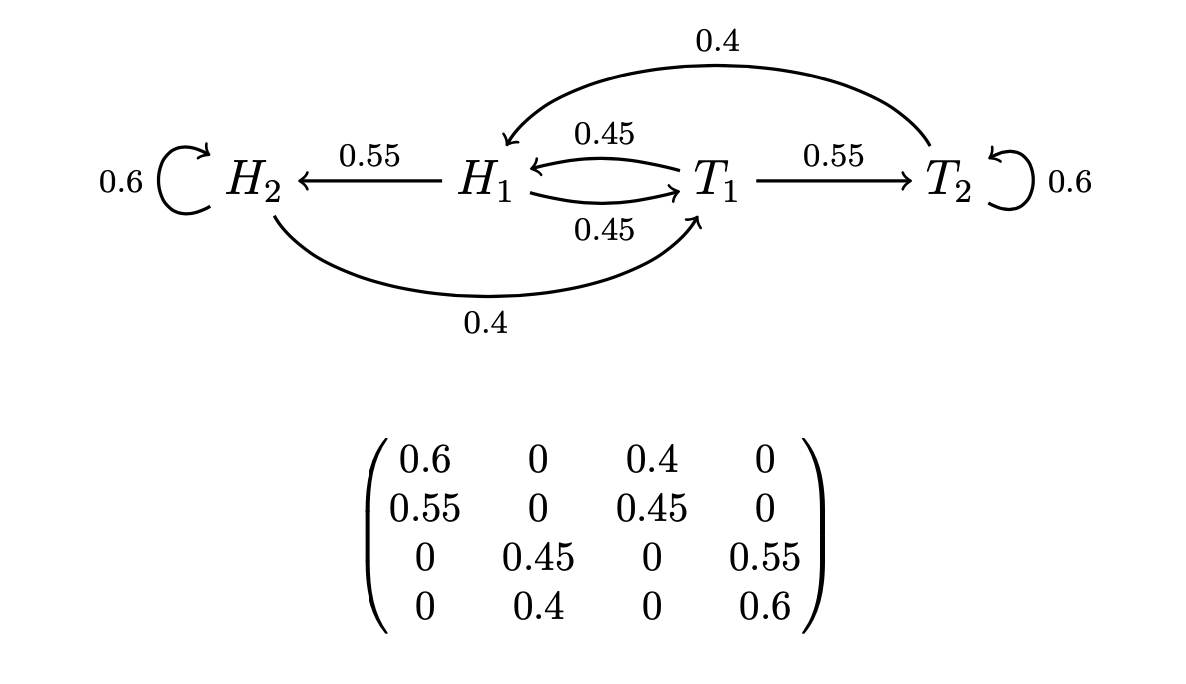

We can represent hypotheses like Steady, Switchy, and Sticky with what are known as Markov chains: a series of states the koin might be in, along with its chance of transitioning from a given state at one time to other states at the next time. For instance, our example of a Switchy hypothesis can be represented like this:

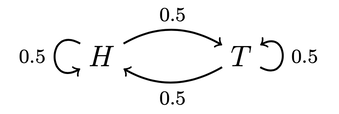

This diagram indicates that whenever the koin is in state H (has just landed heads), it's 40% likely to land heads on the next flip and 60% likely to land tails on the next flip. Vice versa for when it's in state T (has just landed tails). We can similarly represent our Sticky and Steady hypotheses this way:

Given their symmetry, all of these hypotheses will make it so that the koin usually lands heads around half the time. (For aficionados: their stationary distributions are all 50-50.) Since that's all the evidence you have about koins, you should be uncertain which is true.

It follows from this uncertainty that, given your evidence, you should commit the gambler's fallacy: when it has just landed tails you should be more than 50% confident the the next toss will land heads; and vice versa when it has just landed heads. Why? I'll focus on explaining a simple case; the Appendix below gives a variety of generalizations. Let's suppose you can be sure that one of the three particular Sticky/Switchy/Steady hypotheses in Figures 1–3 are true, but you can't be sure which. Suppose you know that the koin has just landed tails (as it has). Given this, you should be more than 50% confident that it'll land heads––you should commit the gambler's fallacy! There are two steps to the reasoning. First, you know that if Switchy is true, it has a 60% chance to land heads; that if Steady is true, it has a 50% chance to land heads; and that if Sticky is true, it has a 40% chance to land heads. So if you were very confident in Switchy, you'd be around 60% confident in heads; if you were very confident in Steady, you'd be around 50% confident in heads; and if you were very confident in Sticky, you'd be around 40% confident in heads. More generally, it follows (from total probability and the Principal Principle) that your confidence in heads should be a weighted average of these three numbers, with weights determined by how confident you should be in each of Switchy, Steady, an Sticky. That is, where P(q) represents how confident you should be in q, your confidence that the next flip will be heads given that it has just landed tails should be:

\[P(H) ~=~ P(Switchy)\cdot 0.6 ~+~ P(Steady)\cdot 0.5 ~+~ P(Sticky)\cdot 0.4\]

Notice: whenever P(Switchy) > P(Sticky), this will average out to something greater than 50%. That is, whenever you should be more confident that the koin is Switchy than that it's Sticky, you should think a heads is more than 50% likely to follow from a tails, and (by parallel reasoning) that a tails is more than 50% likely to follow a heads.

Upshot: whenever you should be more confident the koin is Switchy than that it's Sticky, you should commit the gambler's fallacy!

(1500 words left.)

And you should be more confident in Switchy than Sticky––this is step two of the reasoning.

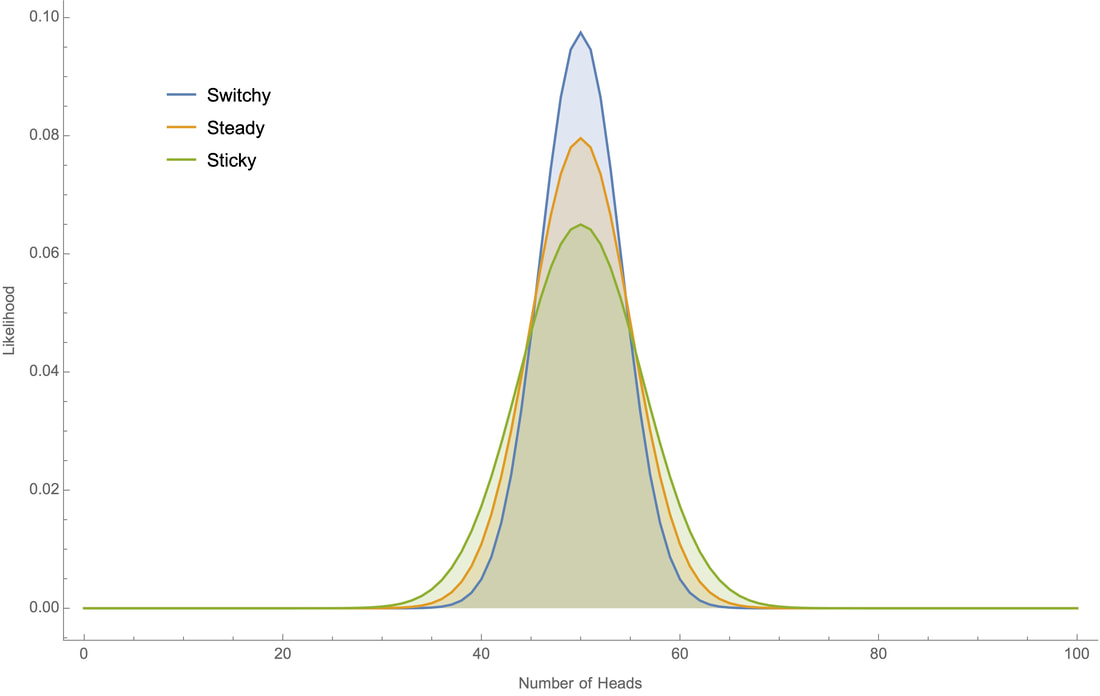

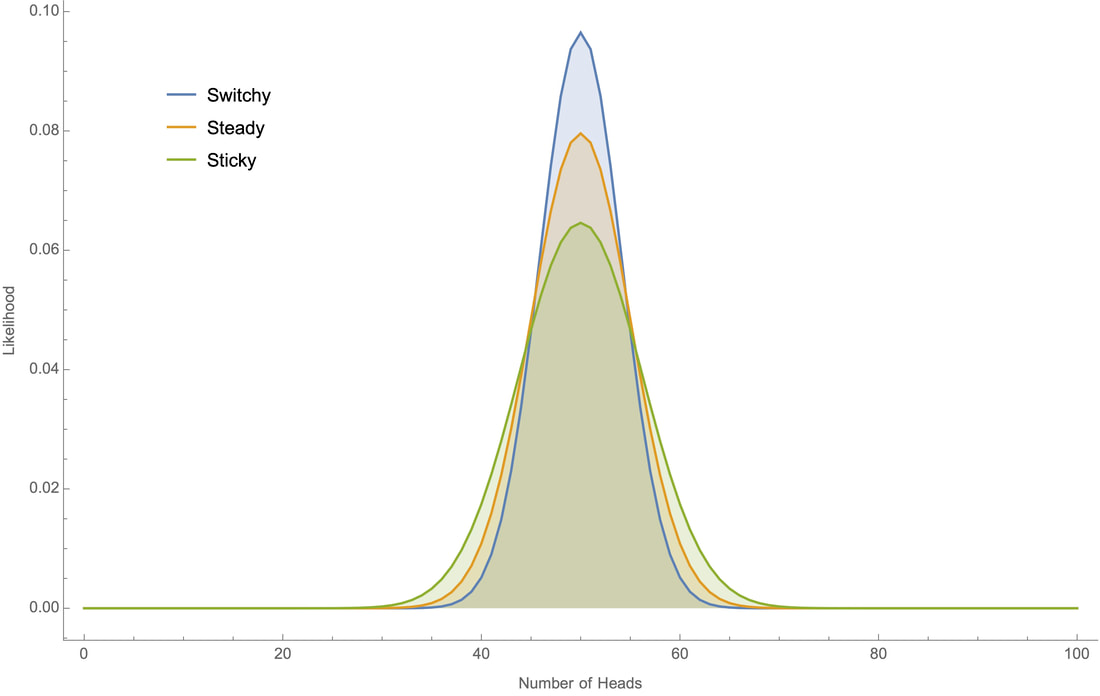

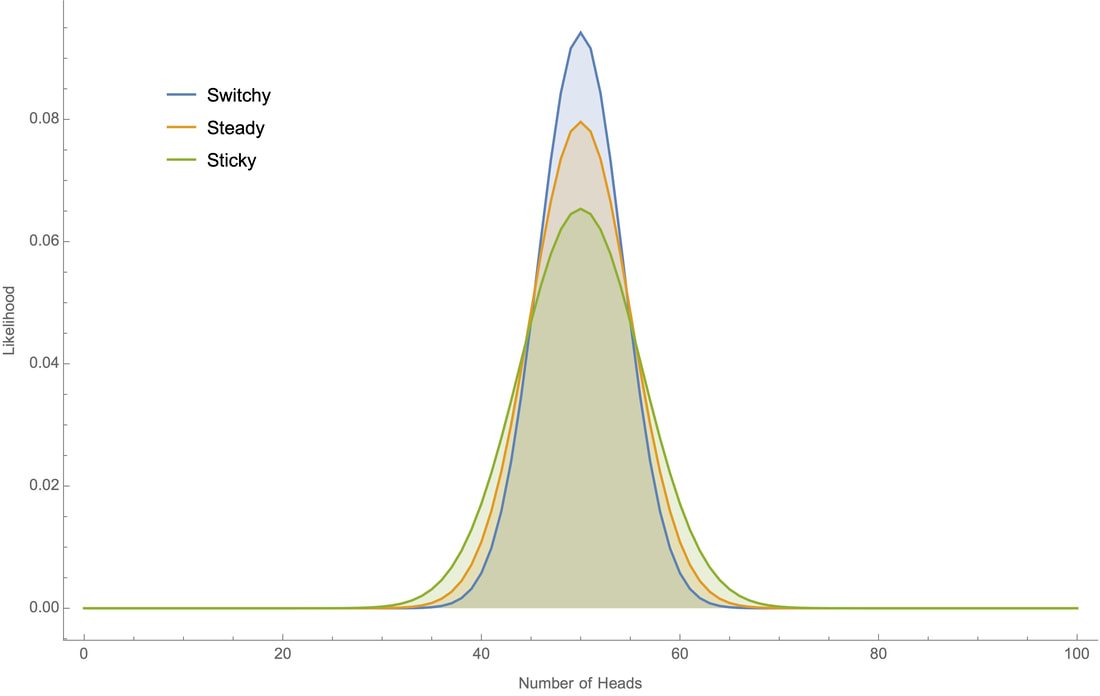

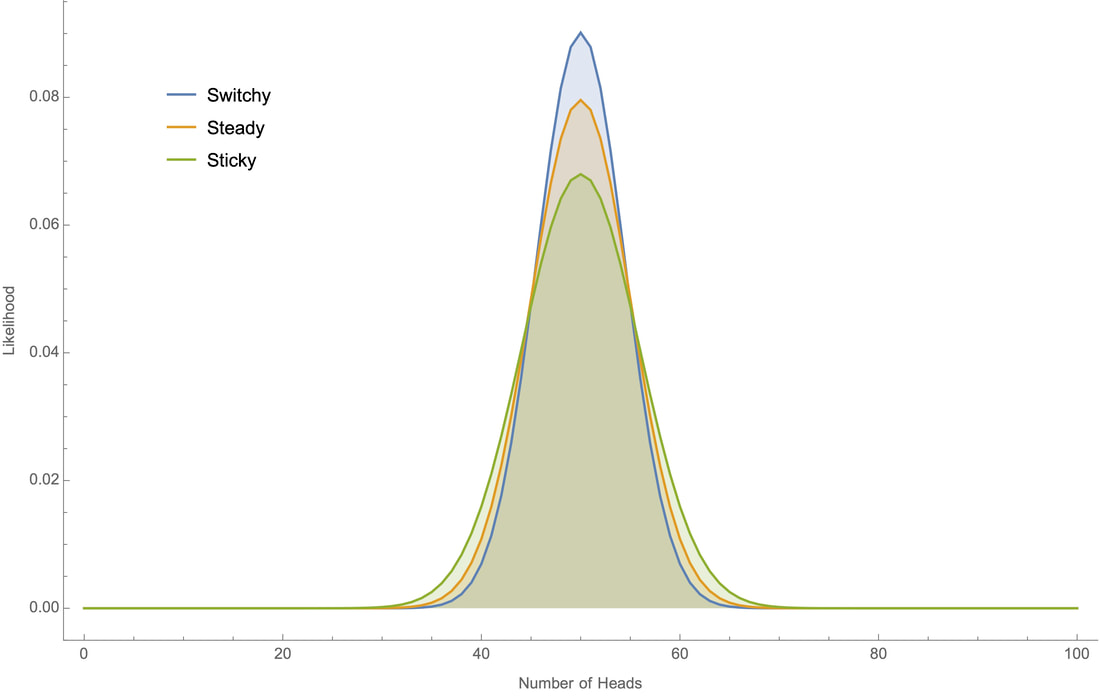

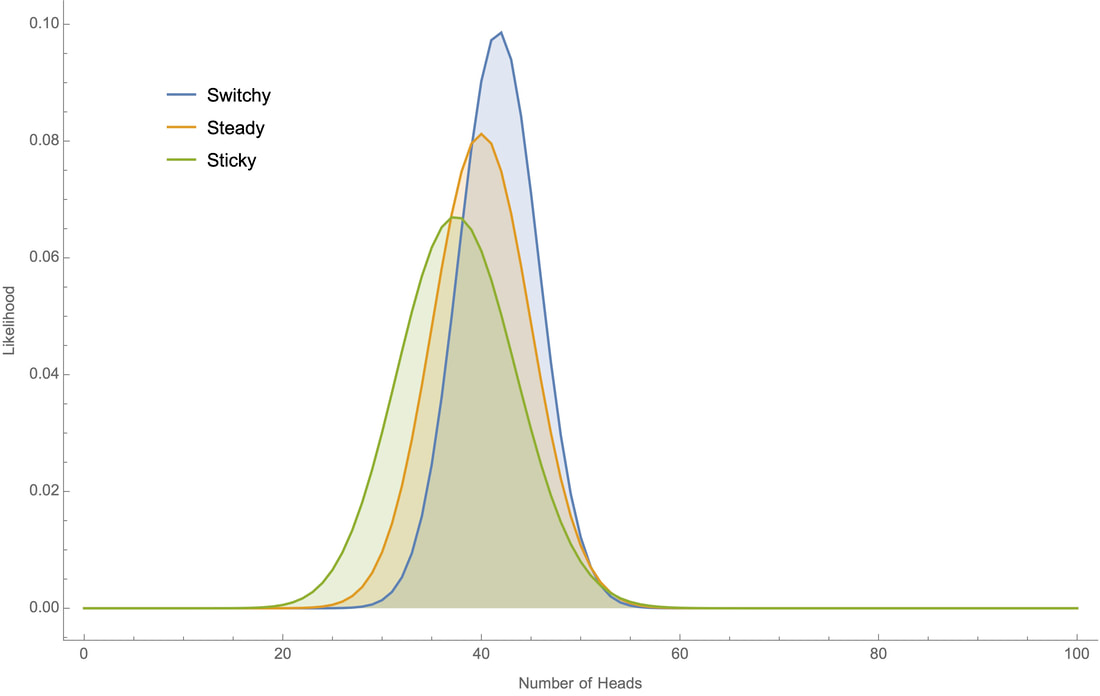

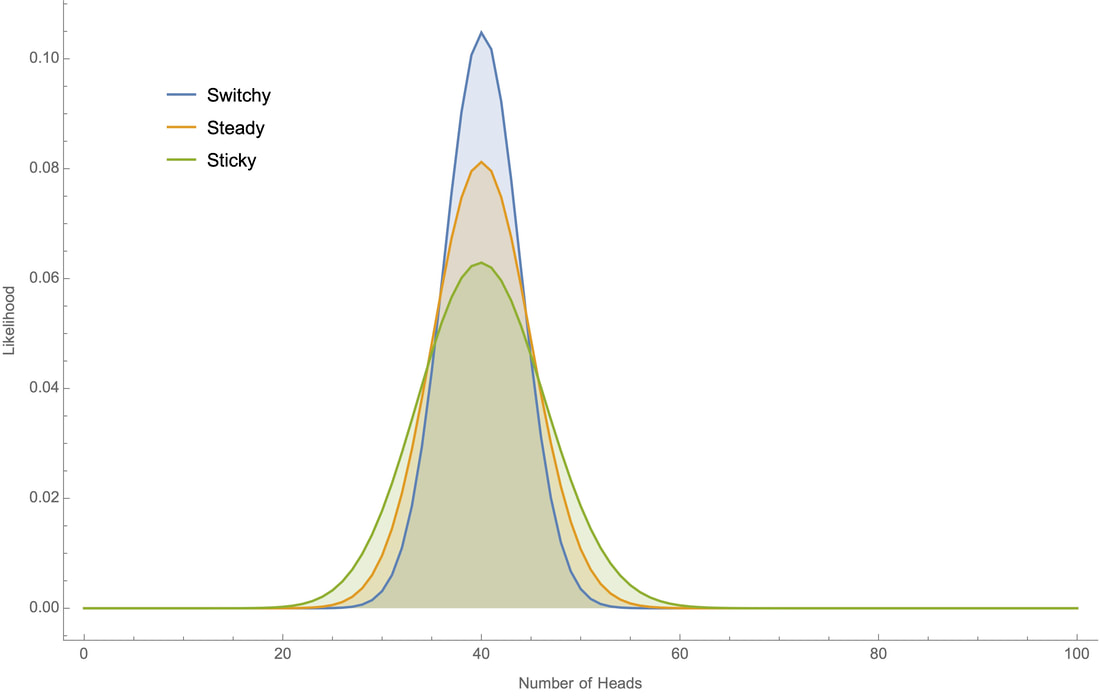

Why? Since you start out with no evidence either way, you should initially be equally confident in Switch and Sticky. And although both of these hypotheses fit with the observation that the koin tends to land heads about half the time, the Switchy hypothesis makes it more likely that this is so––and therefore is more confirmed than the Sticky hypothesis when you learn that the koin tends to land heads around half the time. This is because Switchy makes it less likely that there will be long runs of heads (or tails) than Sticky does, and therefore makes it more likely the overall proportion of heads will stay close to 50%. We can see this in action by working through a small example by hand, and through bigger examples on a computer. Small example first. Suppose all you know about the koin is that I've tossed it twice and it landed heads once. Why does Switchy make this outcome more likely that Sticky? To land heads on one of two tosses is simply to either land HT or TH, i.e. to land one way initially and then switch. Switchy implies that such a switch is 60% likely, whereas Sticky implies that it is only 40% likely. (Meanwhile, Steady implies that it is 50% likely.) Therefore Switchy makes the "one head in two tosses" outcome more likely than Sticky does. It follows, for example, that if you were initially equally confident in each of Switchy, Steady, and Sticky, then after learning that it landed heads once out of two tosses, you should become 40% confident in Switchy, 33% confident in Steady, and 27% confident in Sticky. Plugging these numbers into our above average shows that you should then be a bit over 51% confident that it'll switch again on the next toss––i.e. should commit the gambler's fallacy. The reasoning in this small example generalizes. The closer the koin comes to landing heads 50% of the time, the more ways there are to do this that involve switching between heads and tails many times; meanwhile, the closer the koin comes to landing heads 0% or 100% of the time, the fewer switches there could have been. Switchy makes the former sorts of outcomes more likely; Sticky makes the latter sorts of outcomes more likely. So when you learn that the koin tend to land heads roughly 50% of the time, this is more evidence for Switchy than Sticky––and as a result, you should commit the gambler's fallacy. So far as I know, there's no tractable formula for determining these likelihoods by hand. But since the systems are Markovian, we can use "dynamic programming" to recursively calculate the likelihoods on a computer. For example, if we toss the koin 100 times we can plot how likely each our the three hypotheses would make various proportions of heads:

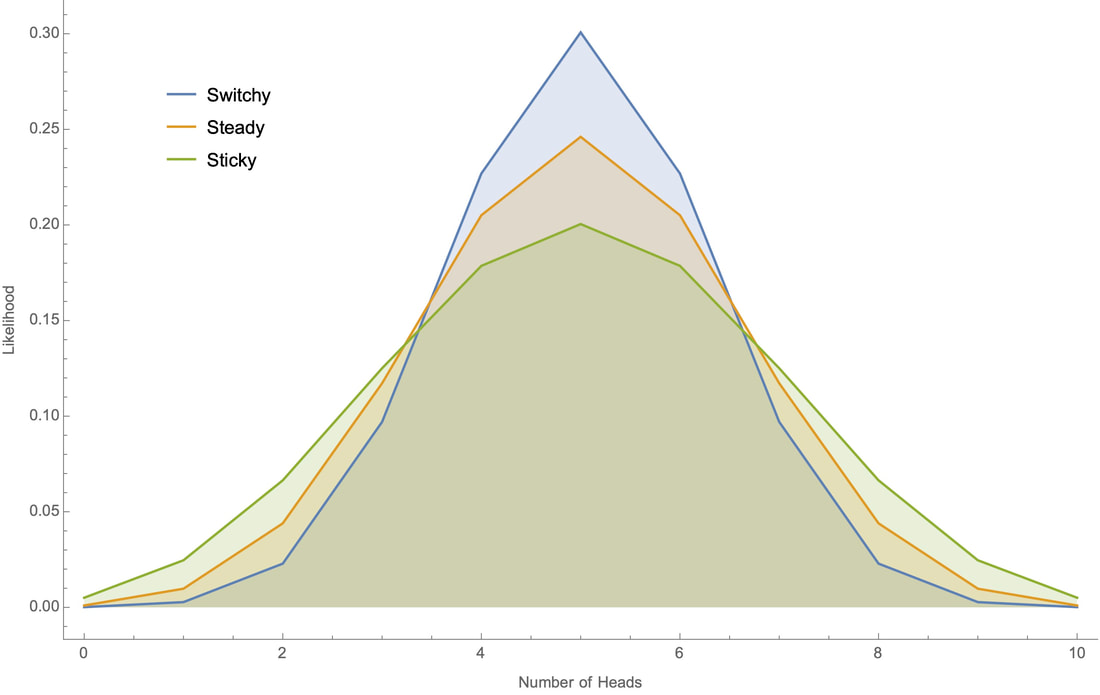

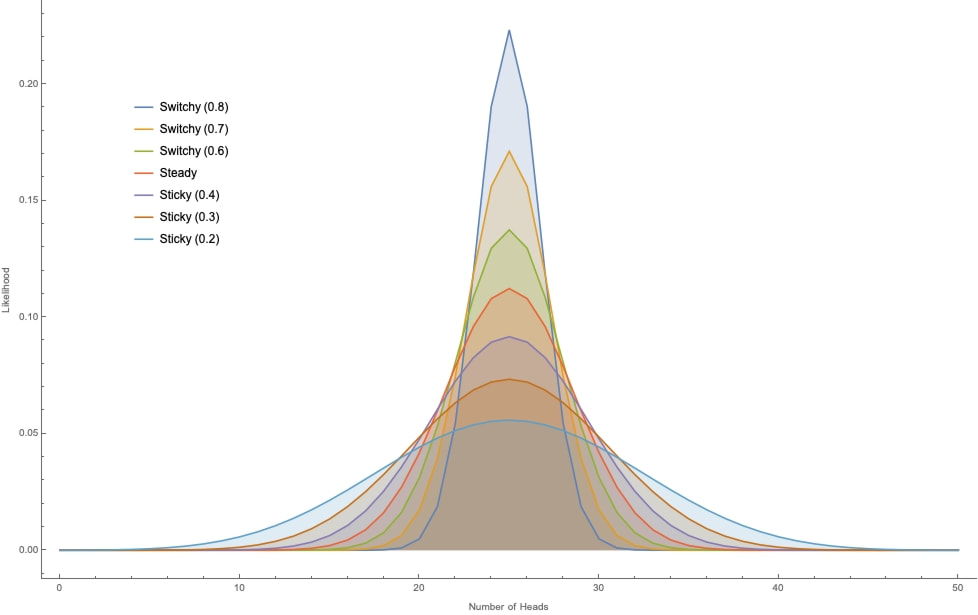

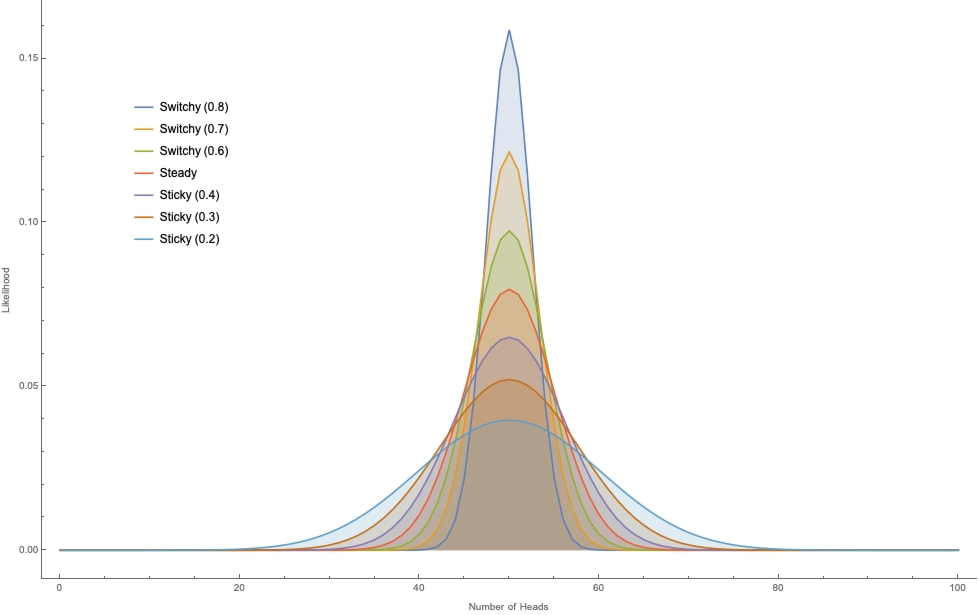

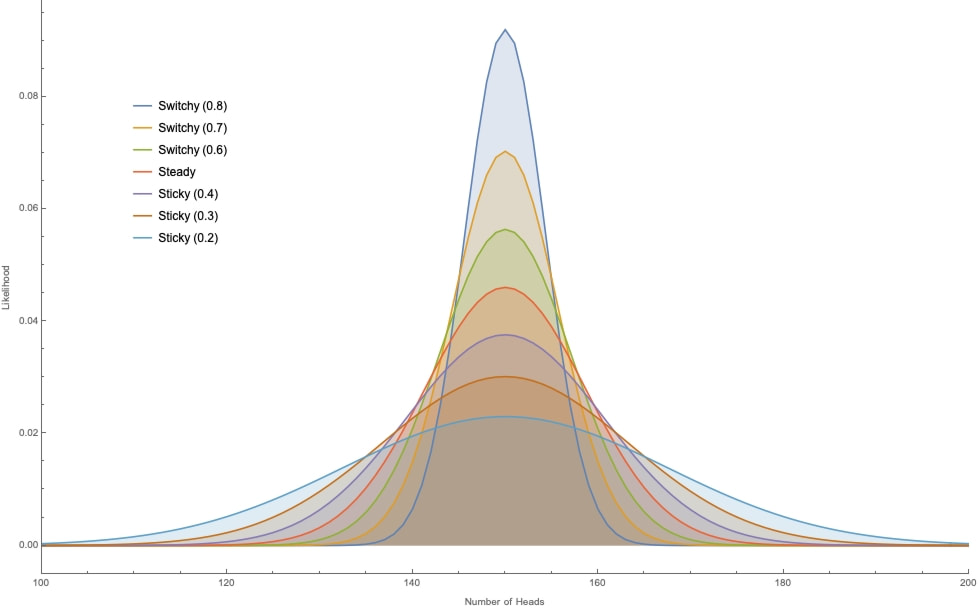

Note that although all three hypotheses generate bell-shaped curves centered around 50% heads, the Switchy hypothesis generates a tighter bell curve around 50% heads.

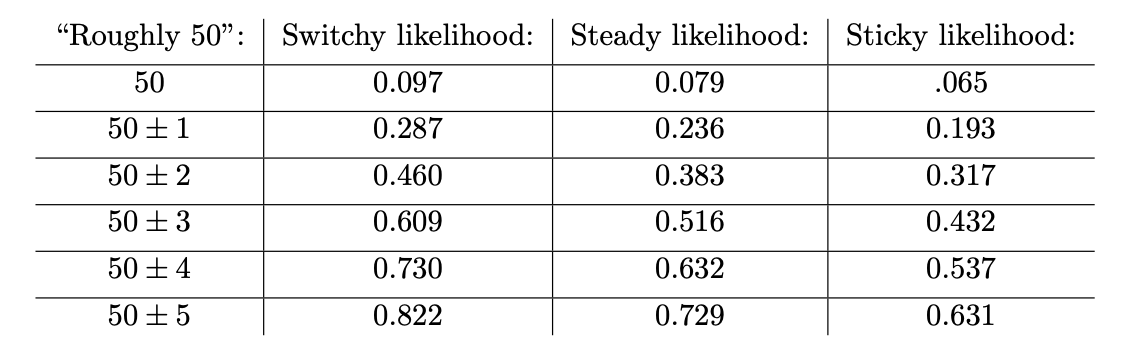

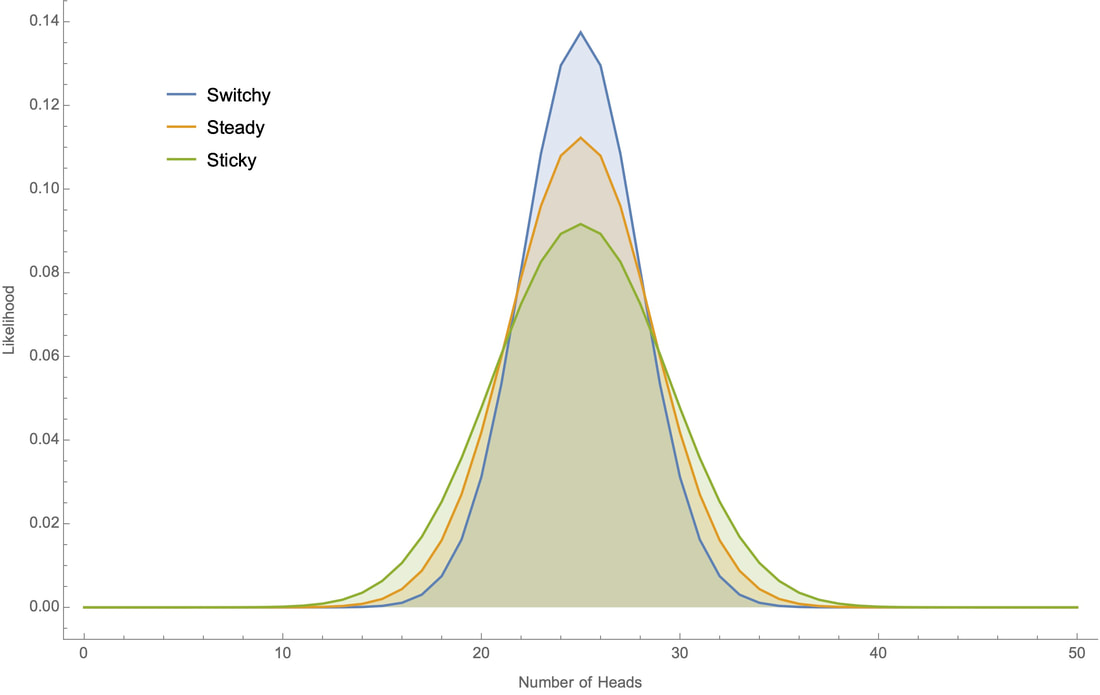

This is the crucial point. Take any precise statement of what you know about koins––namely, that they "land heads around half the time". A precise version of that claim will take the form "the koin lands heads between (50 – c)% and (50 + c)% of the time" for some c. (For example, "the koin lands heads between 48% and 52% of the time.") Switchy generates a higher bell curve that Sticky, meaning it makes any such claim more likely than Sticky does––and therefore is more confirmed by what you know than Sticky is. For example here's how likely each of our three hypotheses would make it that the koin lands heads "roughly 50" times out of 100 tosses, under various sharpenings of the claim:

Since Switchy makes each of these more likely than Sticky, learning that the koin lands heads "roughly 50" of 100 times provides more evidence for the former.

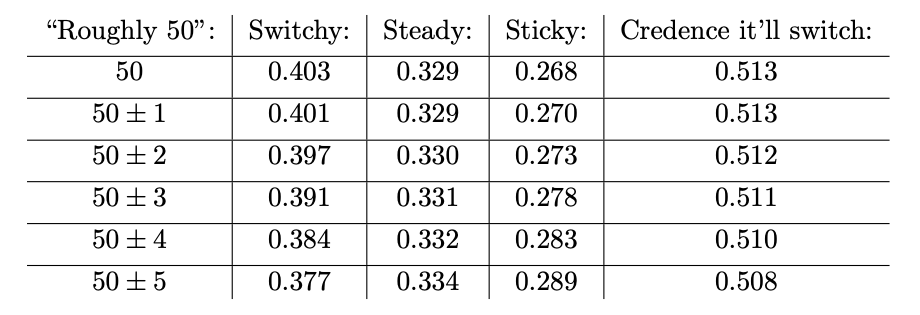

In particular, if you started out ⅓ confident in each of Switchy, Steady, and Sticky, here's how confident you should be in them after updating on various versions of these "roughly 50" claims, along with the resulting you should have that it'll switch on the next flip:

In each case, since you should be more confident in Switchy than Sticky, you should perform the gambler's fallacy.

That said, as has been helpfully pointed out in the comments, as you observe a long string of tails, this provides evidence for Sticky––so sooner or later, that a long enough streak will make it so that you are no longer more confident in Switchy than Sticky. How quickly this will happen will depend on exactly what version of "the koin tends to land heads roughly half the time" you know beforehand. If all you know is "it landed heads on 50 of 100 tosses", a short streak of tails will dislodge your confidence in Switchy, and in fact make it rational to perform the "hot hands" fallacy and expect a tails to be more likely to follow a tails (see the discussion in the Appendix for more on this). But for some versions of "the koin tends to land heads roughly half the time", your confidence in Switchy will be much more robust. Here's one version that's not an implausible characterization of what people often know about processes like this. Suppose what you know about koins is: "on every set of tosses I've seen, it's landed heads around half the time––sometimes very close to 50%, sometimes a bit further. I can't remember the details, but it's always been between 40–60%, usually between 45–55%, and often between 48–52%". If this is what you know, then every one of those sets of tosses provides more evidence for Switchy over Sticky, meaning your confidence in Switchy will be quite robust. For example, suppose you started out ⅓ in each hypothesis and then learned that in 10 sets of 100 tosses each, each set had between 40–60 heads, 7 of them had between 45–55 heads, and 4 had between 48–52 heads. Then you should become 72% confident it's Switchy, 22% confident it's Steady, and 6% confident it's Sticky (see the first "full calculation" section of the Appendix). As a result, you can see a string of up to 7 tails in a row (with no Switches), and still be more confident in Switchy than Sticky––and, therefore, still commit the gambler's fallacy. The Fallacy in Real Life That's what we should say about the gambler's fallacy with koins: it's rational. What should we say about the gambler's fallacy in real life? I think we should say the same thing. Most people don't––shouldn't––be sure of how the outcomes from (most of) the random processes they encounter are generated. Many of these outcomes plausibly are either Switchy or Sticky––for example, whether it rains on a given day, or whether a post on Twitter will get significant uptake, or whether the next card drawn from this deck is a face card. Many others are at least open to doubt. So people––especially those who haven't taken statistics courses––should often leave open that various versions of the Sticky and Switchy hypotheses are true. And since they don't (can't) keep track of the full sequence of outcomes they've seen, what they know about the processes is often much more coarse-grained––e.g. that a given outcome tends to happen around 50% of the time. (See the Appendix for generalizations to other percentages.) As we've just seen, if that's what they know then they are rational to commit the gambler's fallacy. Instead of revealing a basic misunderstanding about statistics, such a tendency may reveal a subtly tuned sensitivity to statistical uncertainty. Of course, this doesn't show that the way real people commit the fallacy is rational: they might commit it for the wrong reasons, or in too extreme a way. (See Brian Hedden's post on hindsight bias for a discussion for how we might probe those questions––and why it is difficult to do so.) But the mere fact that people commit the gambler's fallacy does not, on it's own, provide evidence that they are handling uncertainty irrationally––after all, it's exactly what we'd expect if they were being rational. Objection: What about coins? Obviously coins have no "memory", so when it comes to coins, people should be certain that hypotheses like Switchy and Sticky are false, and instead be certain that Steady is true. Reply: Should they? Should you? Real coins are much more surprising than statistics textbooks would lead you to think. For example, despite the ubiquity of the notorious "coin of unknown bias", it's actually impossible to bias a coin toward one of its sides. Perhaps more surprisingly––and more to the point––it turns out that the way real people tend to flip coins leads them to have around a 51% chance to land the side that was originally facing up. So depending on the procedure you use for flipping your coin repeatedly (do you turn it over, or not, when you go to flip it again?), Steady may actually be false and some version of Switchy or Sticky true! Given subtleties like that, it's rather implausible to insist that someone who has never taken a statistics course nor studied coins in any detail should be certain that hypotheses like Sticky and Switchy are false about real coins, or other more complex gambling mechanisms. As we've seen, so long as they shouldn't be certain of that, they should commit the gambler's fallacy. Conclusion Given people's limited knowledge about the outcomes the random processes they encounter and the statistical mechanisms that give rise to them, they often should commit the gambler's fallacy. So the mere fact that they exhibit this tendency should not be taken to show that they handle statistical uncertainty in an irrational way––if anything, it's evidence that they're handling it as they should! At the least, we need more detailed information about the way and degree to which people commit the gambler's fallacy for it to provide evidence of irrationality. What next? If you have comments, questions, or criticisms, please comment or email me! As I said, this is work in progress. If you want to see more details, check out the Appendix below. For more recent work on the gambler's and "hot hands" fallacy, see this fascinating recent paper. Appendix Here I’ll give some generalizations I’ve worked out, and some discussion of the robustness of these results. The Full Calculation Some people have questioned whether the results holds even in the simple case I focus on in the text, so I figured I'd work through the calculations to show that they do. Take the versions of the Switchy/Steady/Sticky hypotheses we used above. Suppose you are initially ⅓ confident in each: P(Switchy) = P(Steady) = P(Sticky) = ⅓. Now suppose you learn that 50 of 100 tosses landed heads ("50H"). The likelihoods of this given each of the hypotheses are those from Figure 4, reproduced here:

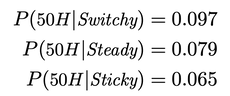

In particular:

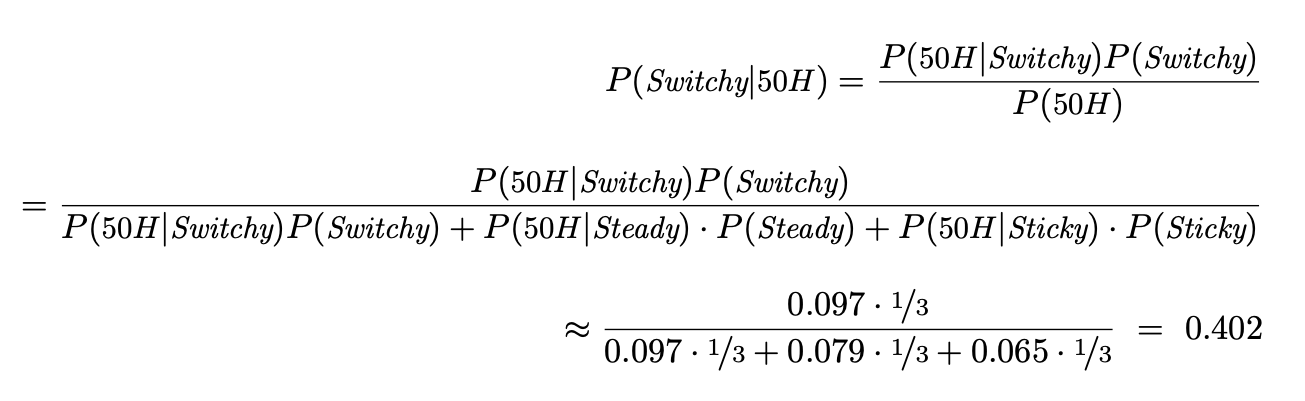

The posterior credences you should have in each hypothesis follow from Bayes rule, which says that:

Parallel calculations show that P(Steady | 50H) ≈ 0.329 and P(Sticky | 50H) ≈ 0.268.

Given that, suppose you've learned that the coin just landed tails. This on its own provides no evidence about Switchy/Steady/Sticky (since you have no information about what state it was in beforehand). Thus your credence that the next toss will land heads should be: 0.403*0.6 + 0.329*0.5 + 0.268*0.4 ≈ 0.513––you should commit the gambler's fallacy. Suppose you have more information about the koin, of the form discussed above. Out of 10 sets of 100 tosses, the koin landed heads between 40–60 times in all of them, between 45–55 in 7 of them, and between 48–52 in 4 of them. (Incidentally, this is what we'd expect you to see if the koin was in fact Steady, and all you remembered was how close it was to 50 heads). The likelihoods of 40–60 heads, given Switchy/Steady/Sticky are 0.99 / 0.96 / 0.91. The likelihoods of 45–55 heads are 0.82 / 0.73 / 0.63. And the likelihoods of 48–52 heads are 0.46 / 0.38 / 0.32. The order doesn't matter, so we can just update by each of these likelihoods the relevant number of times (3 for the 40–60 likelihoods, 3 for 45–55 ones, and 4 for the 48–52 ones). Starting at ⅓ in each hypotheses and updating on your information about the 10 sets of 100 tosses leaves you with posterior credences of P(Switchy) = 0.72, P(Steady) = 0.22, and P(Sticky) = 0.058. Upshot: if your knowledge that the coins land heads "roughly half the time" amounts to knowledge like this––"it always lands heads around 50% of the time, and usually quite close to that"––then you should be much more confident in Sticky over Switchy, and that discrepancy will be robust to seeing a long series of tails in a row, meaning you'll still commit the gambler's fallacy. (In our example, up to 7 tails in a row with no heads and you'll still be more confident in Switchy than Sticky.) Generalizing the hypotheses We can easily generalize the Sticky/Switchy hypotheses. Let Ch be the objective chance of various outcomes, given how it’s landed so far. Suppose you know the koin has landed tails several times in a row, as above. Let H be the claim that it’ll land heads on the next toss. There are three possible alternatives: either the objective chance of heads is greater than, equal to, or less than 50%. So we can (re-)define our propositions:

\begin{align*} Switchy &= [Ch(H)>0.5] \\ Steady &= [Ch(H)=0.5] \\ Sticky &= [Ch(H)<0.5] \end{align*}

It follows from total probability that your confidence should be the following weighted average:

\begin{align*} P(\small H\normalsize ) ~=~ P(\small Ch(H)>0.5\normalsize )P(\small H\normalsize |\small Ch(H) > 0.5\normalsize) ~+~ P(\small Ch(H)=0.5\normalsize )P(\small H | Ch(H) = 0.5\normalsize) \\ ~+~ P(\small Ch(H)<0.5\normalsize )P(\small H | Ch(H) < 0.5\normalsize ) \end{align*}

It follows from the Principal Principle that P(H | Ch(H) > 0.5) > 0.5 and that P(H | Ch(H) < 0.5) < 0.5. In our situation you have no reason to treat these two options asymmetrically, so there should be some constant c such that P(H | Ch(H) > 0.5) = 0.5 + c, while P(H | Ch(H)<0.5) = 0.5 - c. It follows that:

\[ P(\small H\normalsize ) = P(\small Ch(H)>0.5\normalsize )(\small 0.5+c\normalsize ) + P(\small Ch(H)=0.5\normalsize )(\small 0.5\normalsize ) + P(\small Ch(H)<0.5\normalsize )(\small 0.5-c\normalsize ) \]

And again, this value will be greater than 50% iff P(Switchy) > P(Sticky). The trick with using these definitions is that we now need to be careful about what the plausible versions of the Sticky/Switchy hypotheses amount to. We can no longer simply assume they are the 40%-60% hypotheses (from Figures 1–3) I assumed above, so we can’t straightforwardly calculate the likelihoods of various outcomes given Sticky and Switchy. Nevertheless, the plausible versions of these hypotheses will have the same general shape, although some will be more or less extreme in their divergences from 50% probabilities, some may have longer “memories” so that it takes longer streaks to reach these divergences, and so on. See below for direct handling of some of these issues. Robustness Since I have no tractable algebraic expression for the likelihoods generated by various Sticky/Switchy hypotheses—even in the simple cases—there are limits on what I can prove about it. (Hunch: what matters for the difference in likelihoods between Switchy and Sticky is that the former has a shorter mixing time than the latter; perhaps that can be used in a proof? Any mathematicians out there to help a philosopher out?) Nevertheless, it’s easy to check that these results are robust. For example, here are the likelihoods for various proportions of heads from the three simple hypotheses at 10, 50, 100, and 500 tosses. Clearly we are (quickly) approaching a limit in the ratios of likelihoods of 50% heads, and the differences are not washing out.

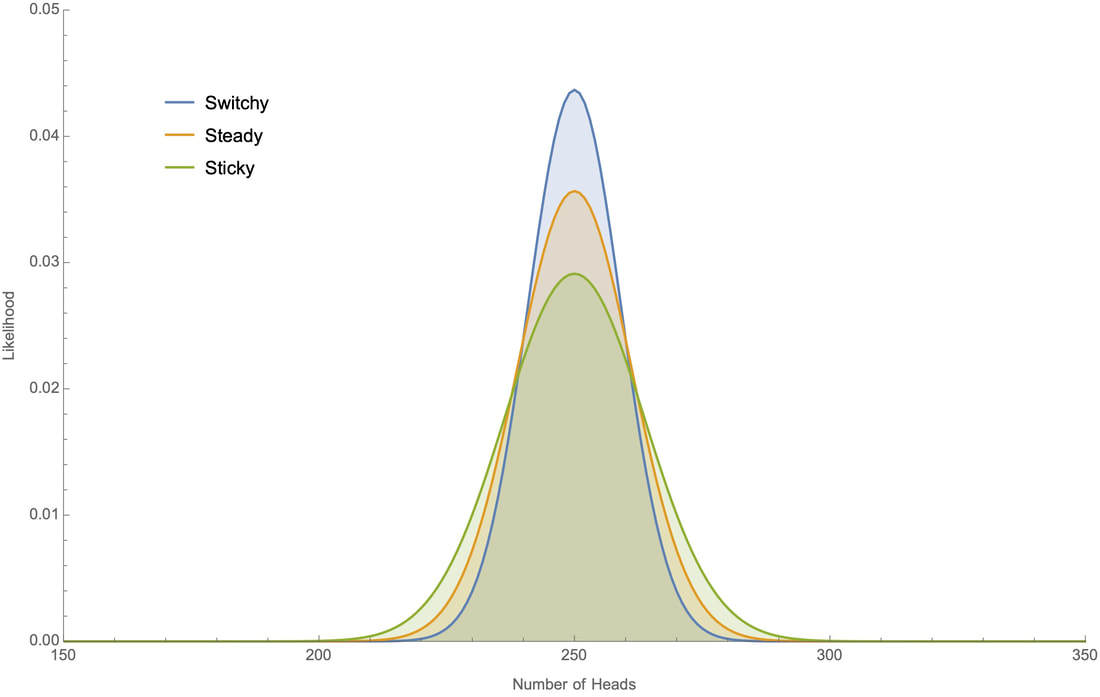

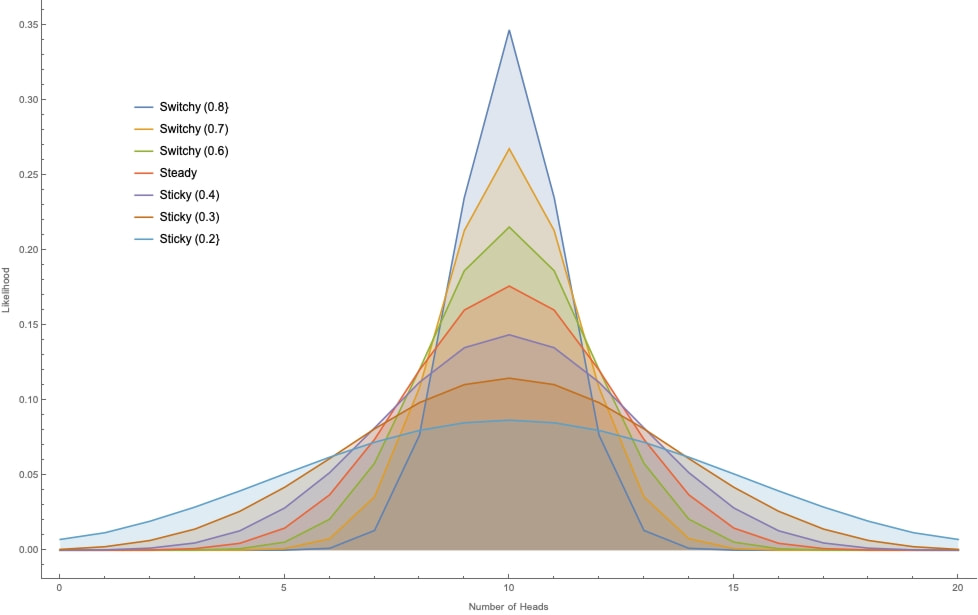

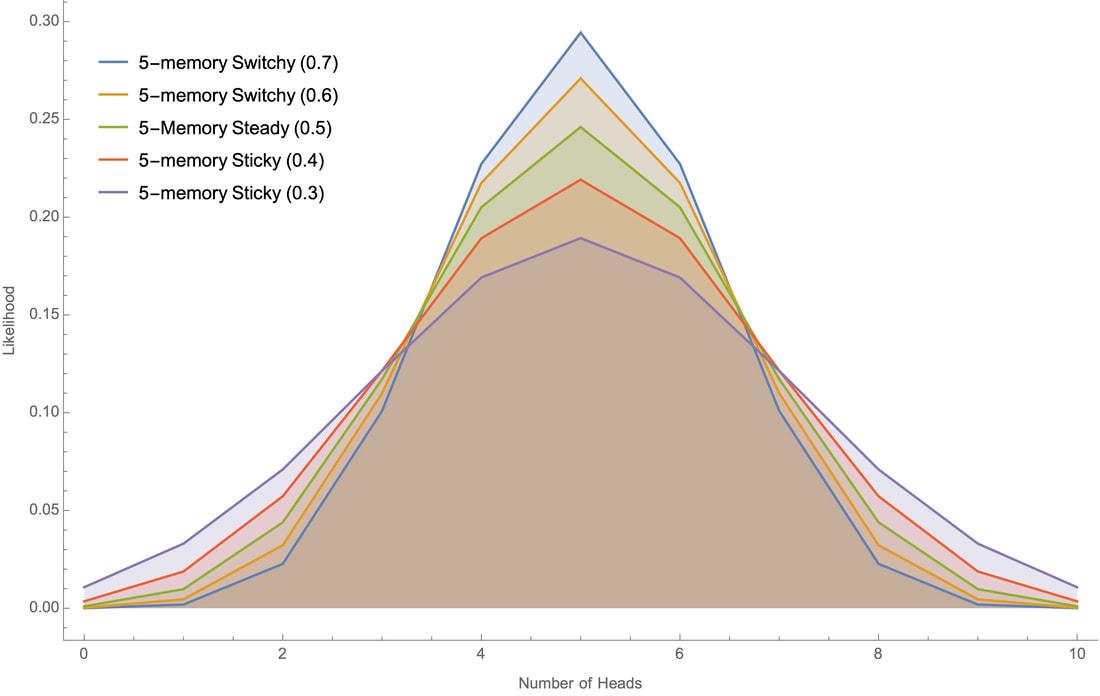

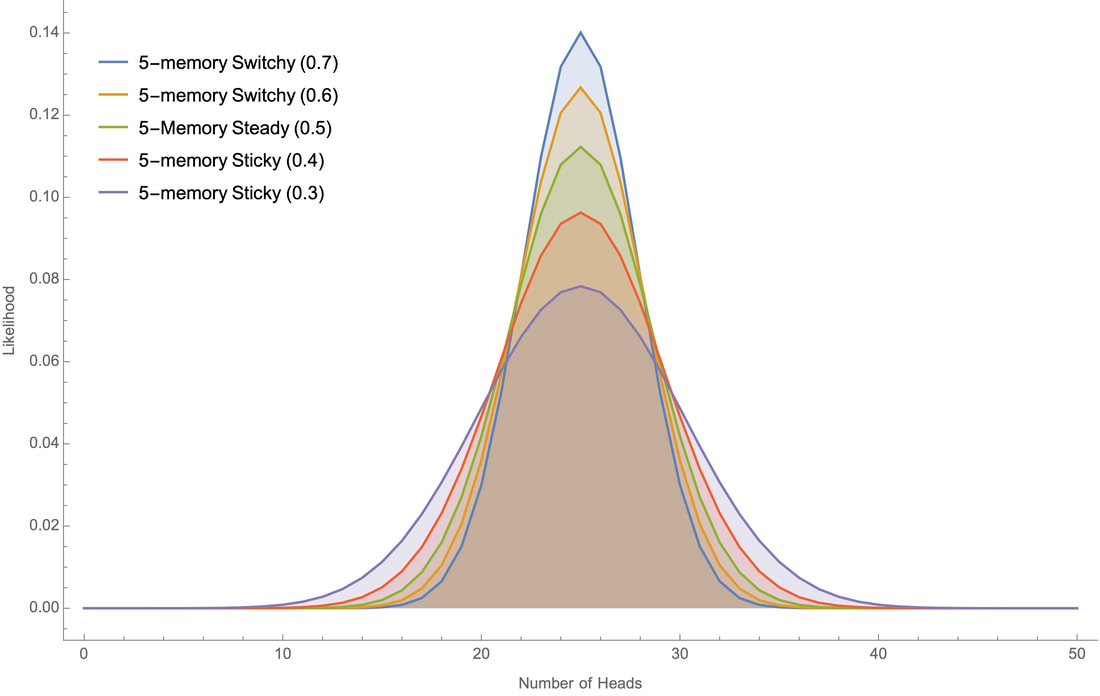

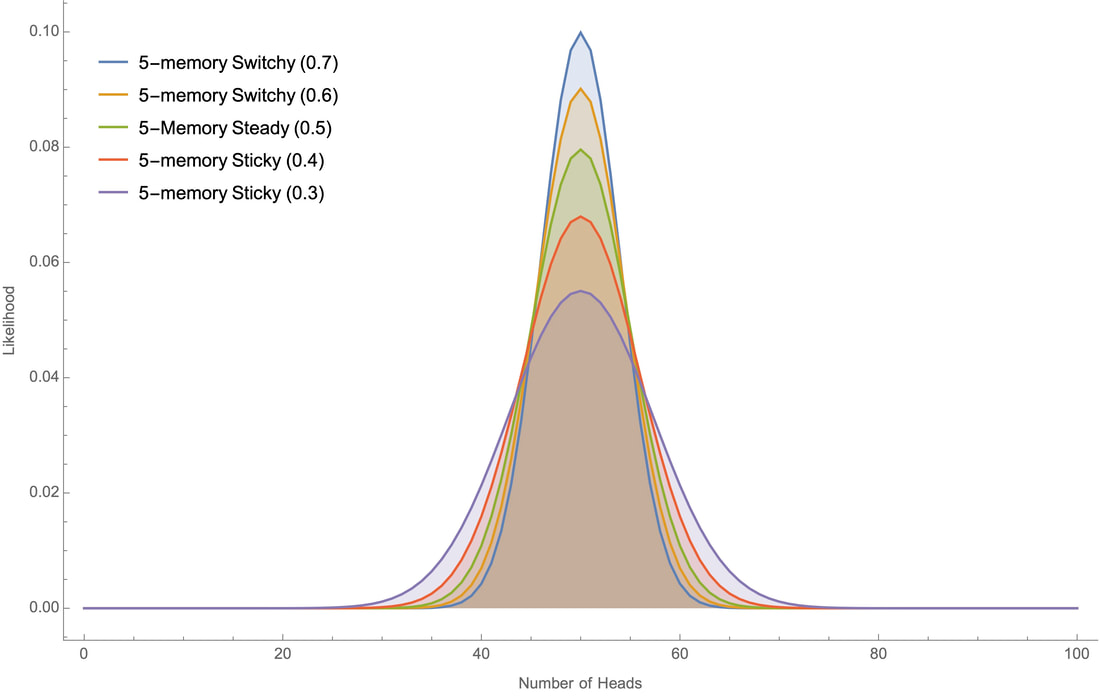

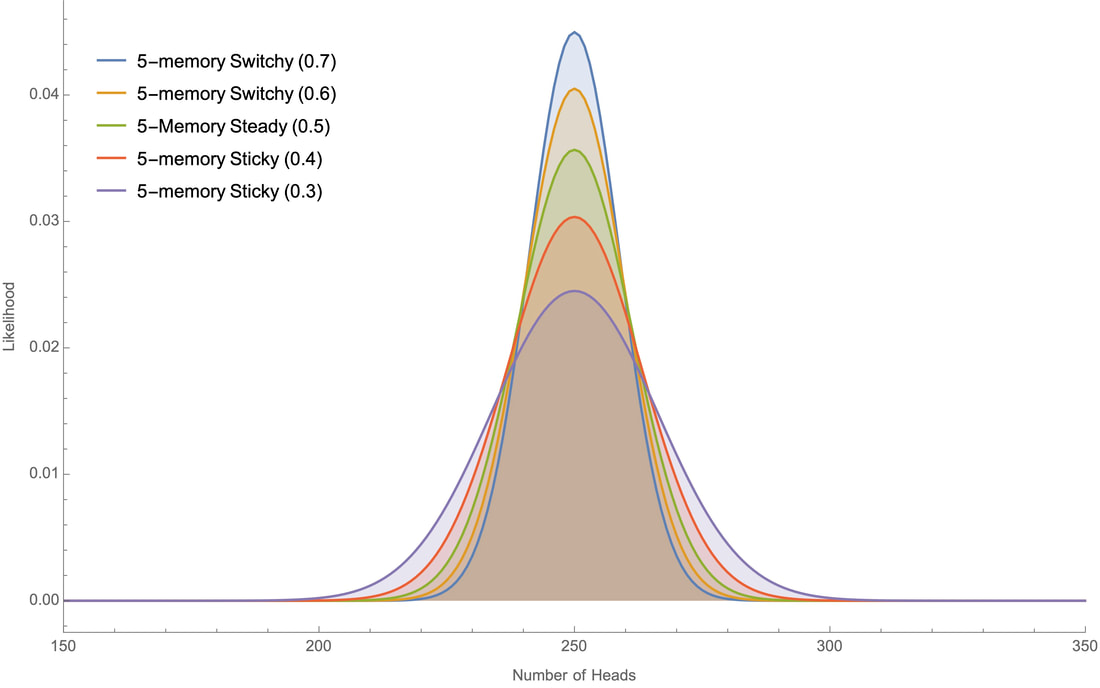

And here are graphs that plot the likelihoods considering Switchy and Sticky hypotheses with different levels of probability of sticking or switching at 20, 50, 100, and 300 tosses (for example, Switchy (0.7) has 70% chance of switching; Sticky (0.4) has 40% chance of switching; etc.):

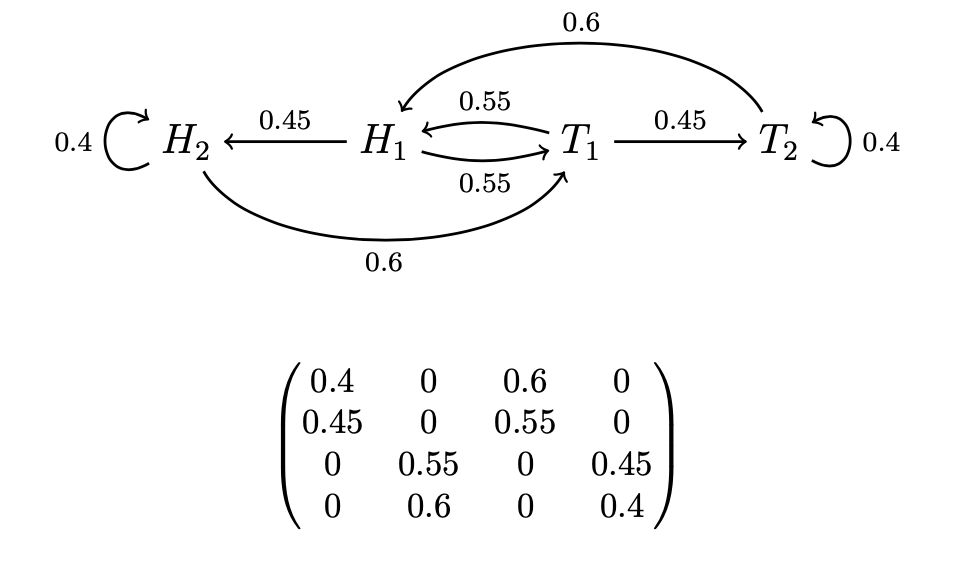

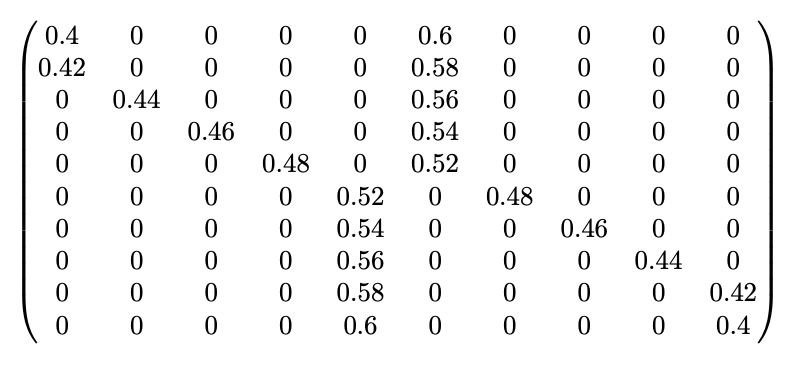

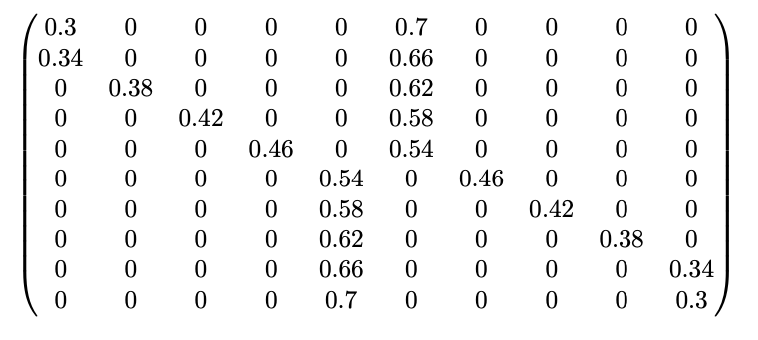

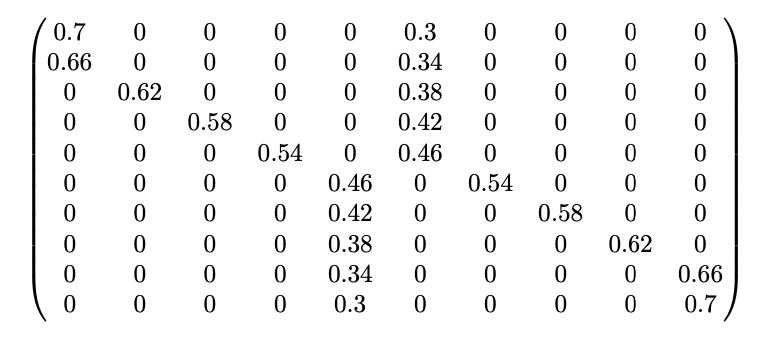

Longer “Memories” The explicit versions of the Sticky/Switchy hypotheses we’ve looked at so far all had “memories” of only size 1—the probabilities of outcomes only depend on how the last toss landed. But both intuitively and empirically, people are much more likely to commit the gambler’s fallacy (or "hot hands fallacy"—see below) with long streaks of outcomes. It’s only when tails comes up 4 or 5 or more times in a row that people start to expect a heads. This can be modeled easily, simply by multiplying the states in our Markov chain. Instead of simply H and T, they will now include how long the streak of heads or tails has been, with the probabilities shifting gradually as the streak builds up. For example, here are diagrams representing 2-memory Switchy and Sticky hypotheses, where the probabilities build to a 60% chance to stick or switch, in both diagram and transition-matrix notation. (For the matrix, row i column j tells you the probability of transitions from state i to state j.) For example, the Switchy hypothesis says that after one heads, it's 55% likely to switch back to tails, and after two or more heads in a row it's 60% likely to switch to tails.

And though I'm not going to try to draw the 10-state diagram, here's the transition matrix for a 5-memory Switchy hypothesis that grows steadily to a 60% switch rate.

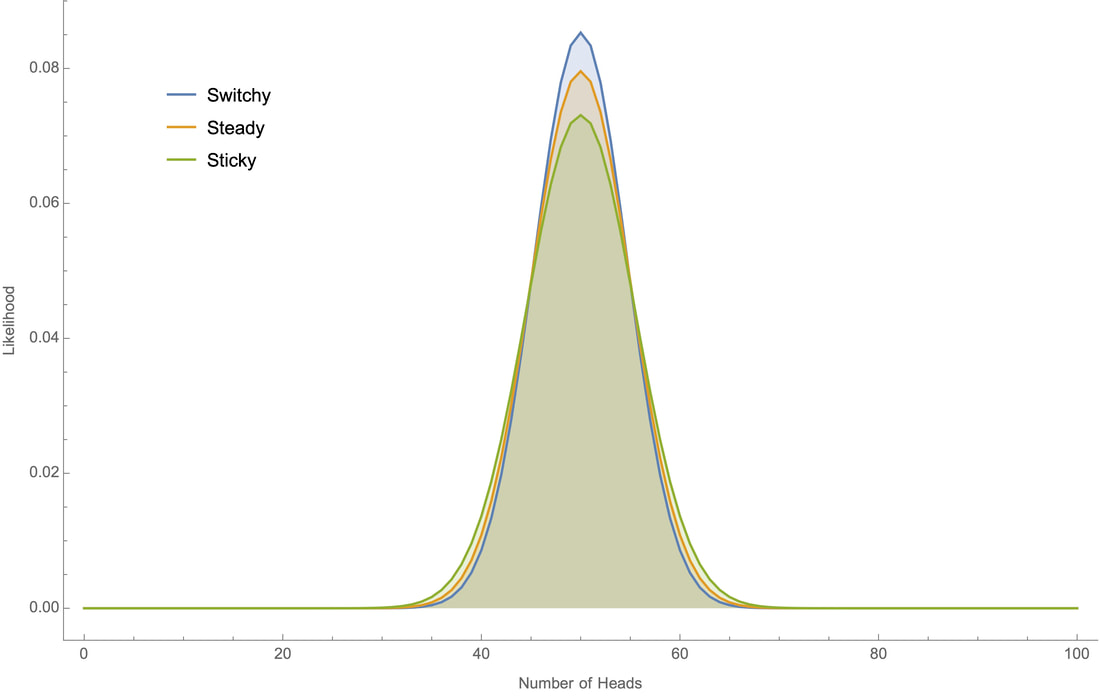

As you’d expect, the qualitative results from these hypotheses are the same as before, but (very) slightly dampened. For example, here are the likelihoods of various outcomes of 100 tosses from our original 1-memory 60% hypotheses (reproduced from Figure 4), vs. the likelihoods of outcomes with the 2-memory, 3-memory, and 5-memory 60% hypotheses:

It’s not until we get "memories" of size 10 or more that we start to see significant dampening of the divergence of likelihoods:

And it's worth noting that the qualitative results will be the same in all these cases, though the degree of gambler's fallacy warranted will decrease as the differences in the likelihoods get smaller.

It seems, empirically, that the versions of the Sticky and Switchy hypotheses that people take seriously are in the 5- to 10-memory range. For robustness checks, I'll show the likelihoods at 10, 50, 100, and 500 tosses for various 5-memory hypotheses whose probabilities move at constant increments up to a given extreme; for example "5-memory Switchy (0.7)" is the chain that takes 5 steps to become 70% likely to switch, and "5-memory Sticky (0.3)" is the chain that takes 5 steps to become 30% likely to switch:

Here are the robustness checks for these and other hypotheses at 10, 50, 100, and 500 tosses:

Upshot: the qualitative results will be the same under these various more realistic versions of the hypotheses.

Hot Hands The “hot hands fallacy” is the tendency to think that an outcome is “streaky” in the sense that if a given outcome happens, it is more likely that it’ll happen again on the next trial. In that sense, it's the opposite of the gambler's fallacy: where gambler's expect things to switch, hot-handsers expect things to stick. (The issue from basketball; see this recent paper for a fascinating discussion of why there were statistical mistakes in the original papers claiming to show that there is not "hot hand" in basketball.) We saw above that when P(Switchy) > P(Sticky), the gambler’s fallacy is rational, and you should be more than 50% confident that the koin will switch how it lands between tosses. By parallel reasoning, whenever P(Switchy) < P(Sticky), it follows that you should be less than 50% confident that the koin will land differently to how it did before—i.e. you should be more than 50% confident that it will land the same way. In other words, whenever P(Switchy) < P(Sticky), you should commit the hot hands fallacy! Upshot: the only time when you should commit neither the gamblers fallacy nor the hot-hands fallacy is when you should be exactly equally confident in Switchy and Sticky: P(Switchy) = P(Sticky). Since such a perfect balance of evidence will be rare, you should almost always commit one of these “fallacies” (though perhaps to only a very small degree). In particular, suppose you start out equally confident in each of Switchy and Sticky, and then learn what proportion of times the koin landed heads in some series of tosses. For example, return to our 100-toss example (Figure 4) with the 40/50/60 hypotheses, and recall the likelihoods:

After learning the proportion of heads out of 100 tosses, should be more confident of Switchy than Sticky iff the blue curve is higher than the green one for the outcome (proportion of heads) you observe, and less confident if vice versa. In fact, there is no outcome of a 100-toss sequence that would make these exactly equal, so given any outcome, you should either commit the gambler’s or the hot-hands fallacy on the next toss.

How can you learn it’s Steady? You might think we’ve run ourselves into bit of a paradox here. Note that in all the graphs I’ve shown, the Steady likelihoods almost never come out ahead overall. In the middle of the graphs, they are dominated by the Switchy likelihoods, and in the edges of the graph, they are dominated by the Sticky hypotheses. This remains true as we crank of the experiment to arbitrarily many tosses of the koins. So… what gives? Does our reasoning show that it’s impossible to learn, by tossing a koin, that it is Steady? If so, it’s gone wrong somewhere. But it doesn’t show that. What it shows is that if all you learn is the proportion of heads, you won’t be able to get strong evidence that the koin is Steady. To get that evidence, you’d really need to look closely at the sequences you observe. There Switchy hypotheses will make streaks very unlikely, while Sticky hypotheses will make repeated flips unlikely, and the Steady hypotheses will strike a balance. If you looked at the full sequence for long enough, you’d almost surely (in the technical sense) get to the truth of the matter about whether the koin is Sticky, Steady, or Switchy. But what we have shown is that without that full data—with only tracking the proportions of heads—people will actually not be able to figure out whether the koin is Sticky, Steady, or Switchy. That is an interesting result. Because real people can’t keep track of full sequences of tosses--at best they can keep track of (rough) proportions. What our results do show is that given only that information, even perfect Bayesians wouldn’t be able to figure out whether the koin is Steady (or Sticky or Switchy). Non-50% versions Every version we’ve looked at so far is one where the number of heads stays around 50%. This is apt for coin tosses, but not so for other chancy events like basketball shots or drawing a face card. We’ll need to generalize what plausible Sticky and Shifty hypotheses look like for processes where the average number of heads (or “hits”) differs from 50%. For example, in the NBA—where the hot hands fallacy discussion is at home—shooting percentages are often around 45%. The reasoning generalizes, but it gets a bit subtle. In the 50% case, all my examples assumed “symmetry” in the sense that the probability added (or subtracted) to getting a heads when it just landed heads is the same as that subtracted (or added) to getting a heads when it just landed tails. This isn’t the right version of symmetry when the Steady hypotheses is no longer 50%. For example, suppose the Steady hypothesis is that no matter how it’s landed, the koin has a 40% chance to land heads on each toss. Then we expect that in the long run, it’ll land heads in 40% of all tosses. So here's our Steady hypothesis:

You might think natural Sticky and Switchy hypotheses centered around this would simply add or subtract a fixed amount (say, 0.1) to the probabilities depending on the state, as before:

But that’s wrong. The “stationary distribution” of these two Markov chains is not 40/60—rather, for the Sticky hypothesis it’s around 38/62 and for the Switchy one it’s around 42/58, meaning that in the long run we would expect them to have these proportions of heads to tails, rather than 40-60. Accordingly, the likelihood graphs are not properly overlapping:

The proper Sticky/Switchy hypotheses if the overall proportion of heads is 40% are ones whose probabilities move depending on where they are, but in a way that leads them to have the same stationary as the Steady hypothesis. I haven’t yet figured out a general recipe for this (any mathematicians care to help?), but here is an example of 1-memory Sticky and Shifty hypotheses that have the correct stationaries:

And here are the likelihood graphs for 100 tosses of these two hypotheses vs. the 40%-heads Steady hypothesis:

Upshot: the same qualitative lessons hold for processes that don't come up "heads" 50% of the time; if all you know is that "roughly x% of the tosses land heads", you should be more confident in (the right version of) Switchy than Sticky, and so should commit the gambler's fallacy.

...Phew! Those are all the generalizations and further notes I have (for now). If you have any thoughts or feedback, please do send them along! Thanks!

25 Comments

Elliott Thornley

5/9/2020 04:48:22 pm

You've convinced me that, if I see a coin land HT, I should believe it has a greater than 50% chance of landing H on the next toss, but (1) I'm not sure this is the 'gambler's fallacy,' as people ordinarily use the term, and (2) I don't think people intuitively believe that the chance of H is greater than 50% in this case.

Reply

Kevin

5/10/2020 07:50:50 am

Interesting! Thanks for these. Here are a couple thoughts:

Reply

Kevin

5/10/2020 11:14:16 am

Thinking a bit more on this: this is super helpful. You're right: even with the background knowledge in place (say, "500 of 1000 tosses landed heads"), the probabilities of Sticky/Switchy are still close enough that runs like this will potentially change the comparison. Turns out that assuming ⅓ in the three 40/50/60% hypotheses I used in the main text, you should commit the gambler's fallacy with "THTTT", but with "THTTTT" you should be even between Sticky and Switchy, and with "THTTTTT" you should actually be more confident in Sticky. So you're right about that––good catch, thanks!

Elliott Thornley

5/10/2020 12:09:54 pm

Thanks for the post! It's a cool topic and I'm looking forward to seeing how it develops.

Kevin

5/12/2020 10:12:24 am

Thanks! Quick update: I added some material (in purple) right before the "The Fallacy in Real Life" section, and then also in the (new) first "Full Calculation" section of the Appendix on this issue. Thanks again or the helpful comments!

Elliott Thornley

5/16/2020 06:43:08 am

Just had a chance to read your full calculation. That's a really cool result!

Mattsthias

5/10/2020 03:47:11 am

Those first four figures under the Robustness section. Do they show the distributions converging? If yes, that means that knowing that heads came up 50% of time in 100 hypothetical prior tosses will give you more skewed priors than knowing that heads came up in 1000000 hypothetical tosses. In other words, what does it exactly mean to say “you know the coin comes up heads 50% of time on average”?

Reply

Kevin

5/10/2020 08:05:20 am

Thanks for your comment! Wrt convergence, I mean several different thing there (should've been clearer). First, they're all converging to putting most of their mass on "roughly 50%"––that's because they all have a 50%-heads stationary distribution. But more importantly for that section, the *ratios of likelihoods* at 50% (and thereabouts) are converging as well: Switchy gives about 1.224 times as much probability to "exactly 50%" as Steady does; Sticky gives about 0.816 times as much probability to "exactly 50%" as Steady does. Since the ratios of likelihoods converge, that means the posteriors will converge as the tosses get larger and larger; if they started out equally likely, learning "50% heads out of N tosses", as N–> ∞, will lead to a posterior in Switchy/Steady/Sticky of around 40.3% / 32.9% / 26.8%.

Reply

Satyaki

5/10/2020 03:14:31 pm

Thanks Kevin. Loved the post!

Reply

Kevin

5/12/2020 10:11:03 am

Thanks Satyaki! Some thoughts/clarifications:

Reply

Jeffrey Friedman

5/31/2020 11:13:17 am

FWIW, I think it's extremely important to be unwilling to take at face value either the logic or the empirics of the mountain of studies that purport to show irrationality (or anything else). The social scientists who produce them are mere mortals and, as one can see by critically inspecting the work of Kahneman and Tversky, are not very good philosophers. You are showing that they can be not very good statisticians, too.

Reply

Kevin

6/2/2020 09:41:02 am

Thanks Jeff! I agree with a lot of what you say (though I think K&T were better philosophers than you give them credit for! I honestly think lots of stuff by them is quite interesting and well-done, even if I disagree with the direction they/ their followers ended up going with it).

Reply

Peter Gerdes

7/14/2020 10:51:40 am

A few points. First, the kind of tricks you applied above can only work so long. Suppose that in fact coins don't show the gambler's fallacy type behavior but that one theory (measures on coin flips) predicts they do. Then conditioning on what is actually observed will keep favoring the standard theory over this alternate gambler's fallacy endorsing view. If you assume you start with some prior probability distribution over some countable collection of such theories I'm pretty confident you can get a nice result that you concentrate all your probability in the limit on theories which don't endorse the gamblers fallacy (or at least don't do so except on some super sparse set).

Reply

Peter Gerdes

7/14/2020 10:58:37 am

In fact why can't I refute your claim thusly. If you really think that, all things considered, it's not irrational to believe in the gamblers fallacy with respect to coin flips then you should be perfectly willing to wager against me at say 2:1 odds (or really any favorable ones) in my favor on the next coinflip not continuing the run whenever there has been a sufficiently long run of heads or tails previously.

Reply

Kevin M

2/2/2021 04:17:11 pm

Hi Kevin D,

Reply

Adam

1/14/2022 10:27:02 pm

This is super interesting! I was wondering if it would be possible to make your code available publically, I would love to mess around with it. THanks!

Reply

Kevin

3/16/2023 10:00:03 am

Sorry I didn't see this till now!

Reply

Neo

2/15/2022 01:05:48 pm

50/50

Reply

Sean

4/9/2022 10:59:17 pm

Conditional probability is about as unintuitive as a subject can be, and it's easy to mistake different conditional probability statements for the same thing. For example, if we *know with certainty*, that the coin is fair, we should commit the gambler's fallacy, because, given the previous streak, we also know that reversion to the mean is inevitable on a long enough timeline. Eventually, the ratio of heads to tails will even out, which implies that (over some scale unknowable to us) the excess number of tails will be balanced out by a surplus of heads. The statement for this would be something like P(H|X,F=1), where H is heads, X is the trajectory up to that point, and F=1 is the knowledge that the coin is fair.

Reply

4/9/2022 11:39:16 pm

Kevin, I think you are not being rational ;-)

Reply

Mujtaba Alam

10/5/2022 11:36:35 am

I think you made a typo here:

Reply

Kevin

3/16/2023 09:00:24 am

Ah, yes good catch, that's a typo! Thanks

Reply

Mujtaba Alam

10/5/2022 11:58:34 am

If you do have a complete sequence, you can model all one-memory hypotheses with a probability of switching as p and the probability of sticking as 1-p, so steady would be p=.5, switchy would be p=.6, steady would be p=.4

Reply

11/23/2022 03:37:23 am

You did a fantastic job at writing it, and your thoughts are excellent. This article is superb!

Reply

McDonald

1/23/2023 02:25:54 am

Jeez....This has to be the longest mental gymnastics anyone has ever gone through just to say "probability dictates the gambling fallacy is wrong". Sure, the odds of a coin landing on heads or tails is 50%, but the probability of flipping a coin and it landing on heads 5 times is not 50%.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Kevin DorstPhilosopher at MIT, trying to convince people that their opponents are more reasonable than they think Quick links:

- What this blog is about - Reasonably Polarized series - RP Technical Appendix Follow me on Twitter or join the newsletter for updates. Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed